By Farag Elkamel, PhD

Introduction

The River Nile is the very lifeline of Egypt. Each drop of its water brings verdant life to the land and its people. There can be no life without the water which the river provides. The Egyptian farmer, who has cultivated this land for seven thousand years, knows this very well. He calls drought “Gafaf”. This word has therefore become the most appropriate description for the loss of bodily fluids and electrolytes necessary for life to continue, that is, dehydration.

Since the television advertising campaign for oral rehydration started in 1984, the Arabic word (Gafaf) which previously referred only to drought has come to mean bodily dehydration. The concept of dehydration became so well known due to television advertising, “that school children, when asked in their final exams in 1986, to write an essay on the drought, wrote instead, on child dehydration.”[1]

Until 1983, Egypt annually lost about 150,000 children due to dehydration. This accounted for half the deaths of children under five.[2] This tragedy can be averted by treatment with a simple mixture of salt, sugar, and water. This mixture is called Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) which was made available in all hospitals and primary healthcare centers in Egypt since1977. The situation before the National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Project started its activities in 1983 was as follows:

- ORS was supplied by UNICEF and WHO, and local facilities necessary to produce the required amounts of ORS to meet the real need were not available. Furthermore, the size of the available ORS packets was intended for use at health facilities as it requires a liter of water to be dissolved in with the intention of rehydrating several children simultaneously.

- The majority of physicians in Egypt, including pediatricians, did not believe in oral rehydration therapy and depended on intravenous solution in the treatment of dehydration. They also advised mothers to stop breastfeeding and food for twenty four hours or more, and heavily prescribed antibiotics and ant diarrheal medications.

- The majority of mothers did not know what dehydration was, neither were there aware of the oral rehydration treatment (ORT). In addition, they and used various incorrect methods to treat diarrhea, including depriving the child with diarrhea from liquids altogether.

- Services for the treatment of dehydration were not available in all health centers nationwide.

NCDDP and Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) Campaign (1983-1989)

National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Project (NCDDP) began in 1983 as a social marketing project with the objective of producing, distributing, and promoting ORS in order to reduce infant mortality caused by dehydration. When I started the job as technical adviser and director of the communication campaign, , the project had been in place for a few weeks. Some plans had already begun. Two important decisions had been made that concern the communication strategy: the first was to start a pilot campaign in the northern city of Alexandria that focused on the use of radio, and the second was the establishment of a communication committee that included some ministry of health officials as well as press reporters. Eventually, I challenged and changed both plans. In fact I radically changed other project strategies as well.

First, I realized after one meeting with the “communication committee”, which was already in place before I started the job, that it was more of a committee of beneficiaries. When we discussed the communication strategy during the meeting, each reporter adamantly insisted that the campaign can only succeed if a daily or weekly advertisement is placed in their newspaper or magazine. Representatives of the ministry of health in the committee didn’t object.Press reporters were very important for the ministry. They cooperate in publishing favorable reports and news on the ministry and the Minister himself.

However, the vast majority of the project’s target audience didn’t read those newspapers or magazines. I was quite sure of that because only three years before, I had just undertaken a major national survey that explored media habits of the Egyptian public in great detail. I explained to the project leadership that the committee represents a case of conflict of interest, and suggested to him that it should be abolished. I was pleasantly surprised that he agreed.

In addition to print media, the survey also showed that radio was losing ground to television in Egypt. When I joined the project, I discovered that its communication strategy had identified radio as the main medium to reach mothers. The “American Adviser” was the “Academy for Educational Development (AED) who dispatched Elizabeth Booth to plan and implement the first pilot radio campaign in the northern city of Alexandria, using that city’s local radio station.

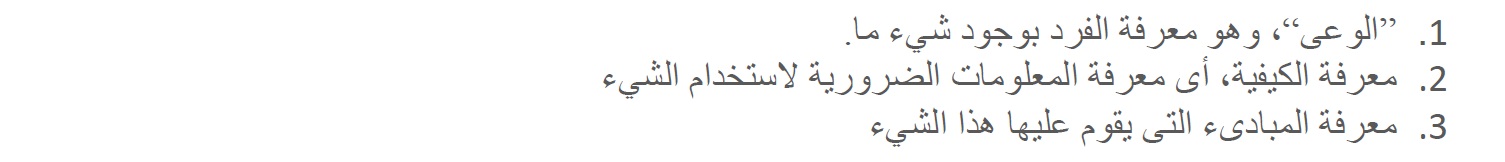

But I developed a new communication strategy[3] that specifically stated that television advertising “will prove to be the most effective activity in reaching the target audience”[4] which consisted primarily of mothers of children below five. This expectation was based on the fact that television sets existed in over 90 percent of Egyptian households, and TV. was watched especially more regularly by the rural and poor segments of the target audience, the majority of which is illiterate, and cannot be reached through print media. While I disagreed with the existing plans, I had to supervise the implementation of that pilot campaign, but worked on an alternative communication strategy. Following is the communication strategy which I drafted for the project in August 1983. It should be indicated here that this revised strategy was based on the theoretical framework presented in the author’s model of “knowledge and Social Change”[5] The model, its applications and methodology are reviewed elsewhere[6] and is illustrated in the diagram shown above.

The Revised Communication Strategy

I. OBJECTIVES

To teach, persuade, and change the behaviors of (a) all mothers of children under five, and (b) other specific target groups, especially health personnel, mass media reporters, and decision makers, with regard to the management of diarrhea and dehydration. In order to attain these objectives, these audiences must be infirmed in both efficient and effective ways. Information which must reach these audiences can be classified into three types of knowledge;

A. AWARENESS-KNOWLEDGE

- Diarrhea is a disease which can lead to more serious ones.

- Two kinds of diarrhea are known to exist. The serious one is watery diarrhea or “eshal zayy el mayyia,” which is usually accompanied by vomiting and gastroenteritis or “nazla maawia.”

- Diarrhea can lead to dehydration “gafaf” which is very serious and can lead to death.

- There are different degrees of “gafaf.” “Gafaf” is easier to treat in its early stages.

- Only serious “gafaf” needs special treatment in hospitals and health centers. Mild cases can be treated by mothers at home.

- You will be able to recognize it if your child has gafaf. The child will vomit, will have sunken eyes, dry skin, no appetite, and will be weak.

B. HOW-TO-KNOWLEDGE

- Complications of diarrhea can be prevented if the child is given plenty of liquids during diarrhea.

- Food and/or breast milk must continue during diarrhea to give the child strength.

- Examples of liquids to give the child during diarrhea are soups, juices, or soft drinks. Examples of food to give are vegetables, fruit, and rice.

- Children who have watery diarrhea “eshal zayy el mayyia” must take ORS “Mahloul Moaalget el Gafaf (MMG).” You can buy this “Mahloul” from the pharmacy for a few piasters, or even get it free from hospitals and MCH centers.

- You must dissolve the MMG solution right; otherwise it will not be effective. To be sure, read the instructions on the box and ask your doctor, pharmacist, or nurse to tell you how to dissolve the solution right.

- Give your child the solution slowly and gradually, not in large quantities at once. Give at least two full spoons every five minutes.

- Gafaf can be very serious. If your child is constantly vomiting and looks very dehydrated, it must be taken to a doctor or hospital at once.

C. PRINCIPLES-KNOWLEDGE

- Diarrhea may be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, etc. Factors that make it prevail include poor personal hygiene, poor food preparation, contaminated water, and flies.

- Dehydration is the loss of body fluids and essential salts and minerals. This happens because of acute diarrhea. Unless restored, this loss of body fluids, salts, and minerals seriously affects the fragile body of the child, resulting, perhaps, in death.

- NMG will restore the child’s appetite to eat; and food and milk will strengthen the child. MMG, food, and liquids restore the lost body fluids, salts, and minerals, thereby protecting child against dehydration.

- Certain kinds of food will also help stop diarrhea faster, in addition, of course, to strengthening the fragile body of the child.

- When your child has diarrhea, your first worry should be to prevent dehydration, not to stop diarrhea. Diarrhea will eventually stop, but depending on what you do, your child may or may not get gafaf, which is your child’s number one enemy.

- Severe dehydration can negatively affect the health of a child, his growth, and his mental development. A good and loving mother therefore never lets her child get dehydrated.

Il. CHANNELS OF COMMUNICATION

Characteristics of the main target audience (mothers of children under five) are pretty well known. The majority are illiterate and live in low-income urban areas. Only wise and planned use of communication will enable them to get the project messages outlined above. There is enough evidence from different media surveys conducted in Egypt to prove that only innovative social marketing techniques would succeed in reaching the target audience.

Print media, as well as health programs on radio and television should be used very lightly and with extreme caution, because they reach a small, and a particular segment of the target audience. Advertising in the print media should be kept at an absolute minimum, if at all. Interpersonal communication should be utilized in teaching doctors, pharmacists, social workers, as well as other health personnel.

The following social marketing activities should be carried out either directly by the project or through competitive bidding according to specific Requests for Proposals (RFP’s) issued by the NCDD Project:

- Development and production of audio-visual aids and other training materials for doctors, pharmacists, and other health personnel.

- Development and production of radio and television spots and special programs for the main target audience.

- Development and production of booklets, posters, pamphlets, billboards, etc.

- Planning and organization of national and regional conferences for doctors, pharmacists, and other health related decision makers and national and community leaders.

- Design and execution of special person-to-person communication campaigns with particular groups and in problem areas.

- Development, production, and distribution of certain point-of-sale and promotional items.

- Securing and producing testimonials advocating ORT by prominent doctors and famous personalities.

III. GUIDELINES FOR SOCIAL MARKETING

A. Message Design.

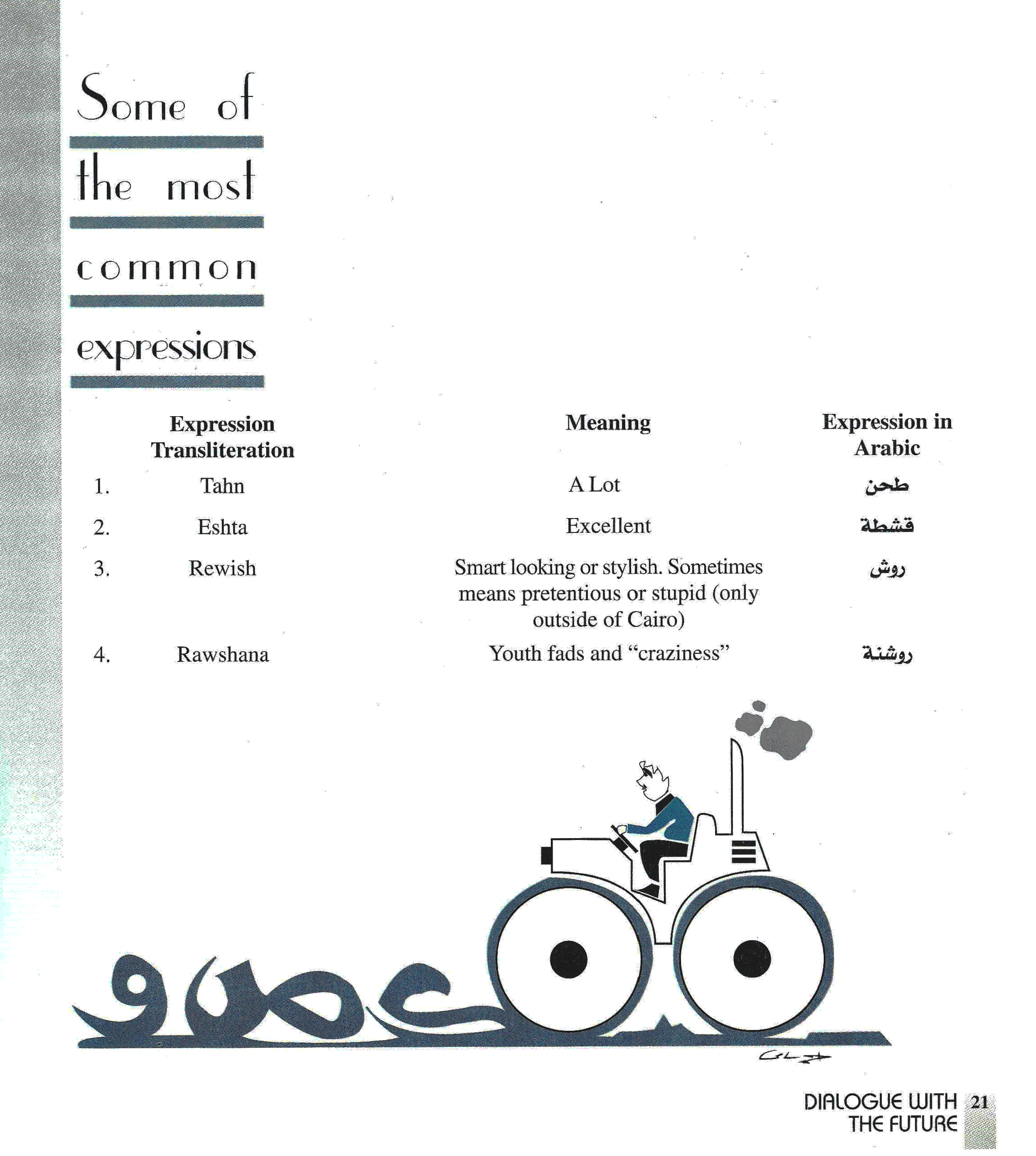

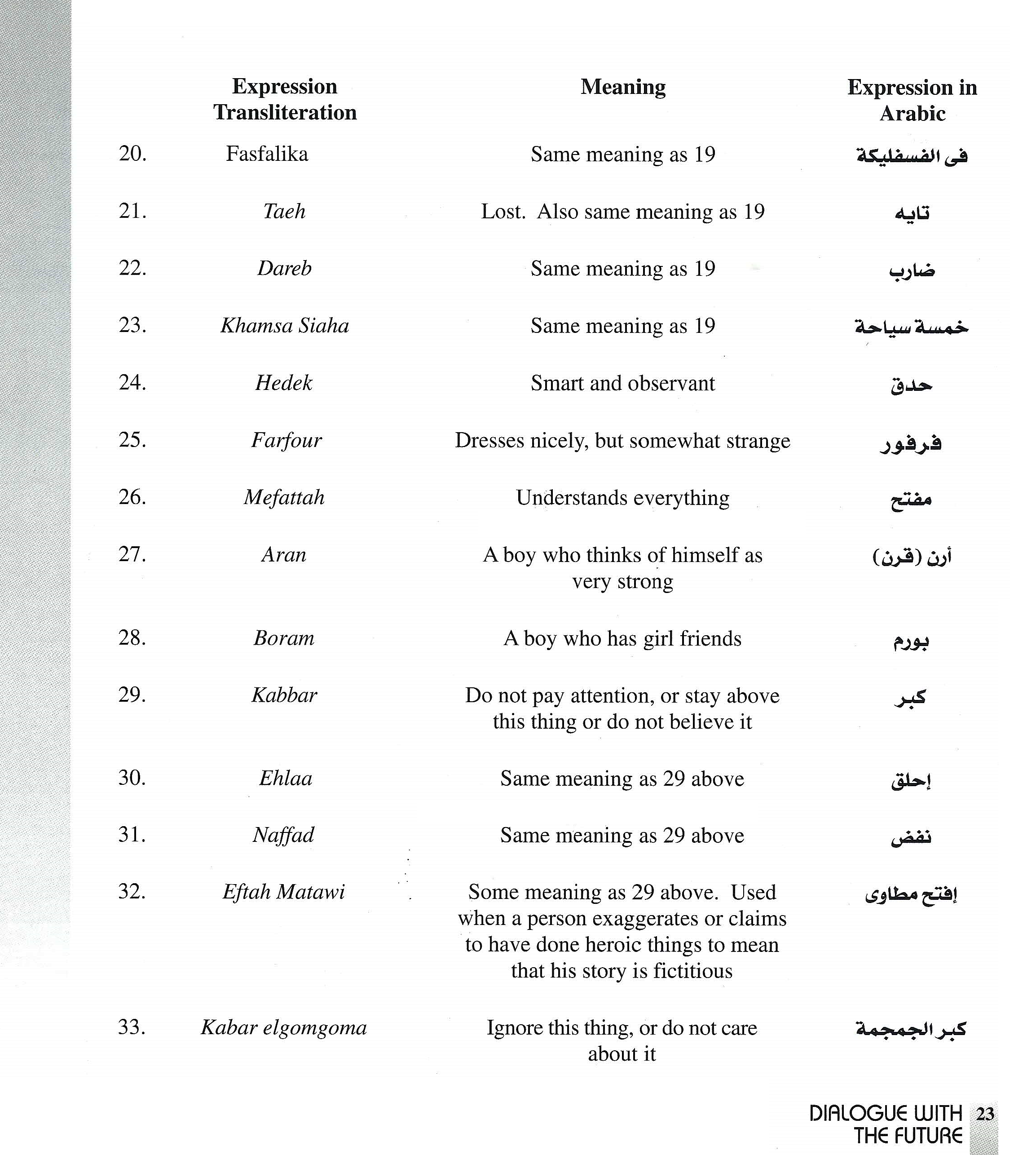

Characteristics of the main target audience will have to be observed in designing social marketing communication. Messages must be appealing to this general audience, and the information contained in the message should be clear and phrased in simple, non-technical, colloquial Arabic.

B. Format and Time of Broadcast

Time of broadcast can be very decisive in affecting the success of spots and special programs to reach the target audience. It is important to note that the most popular format both on radio and television is drama, a fact which can be exploited by the project in at least two ways. First, ORT messages, spots, and special programs would perhaps attract a larger audience if produced in the form of drama. Second, any spots, commercials, or special messages will reach more viewers and listeners if aired during, before, or immediately following soap operas, movies, or ether popular entertainment programs and shows.

C. Theme

All ORT messages communicated by the NCDD project should be designed to appeal to mothers, who should be described as caring, loving, and smart, and certainly not as negligible or ignorant. In communicating with doctors and other “elite” target groups, the theme should be the scientific or medical “revolution” resulting from ORT.

IV. ORGANIZATION OF CAMPAIGN ELEMENTS

In addition to person-to-person communication as described above, the project’s mass communication activities can be classified into four rather different elements which complement each other:

- News releases and public relations on behalf of the project. This campaign activity involves the publication and broadcast of feature stories and news highlighting project activities, the opening of rehydration centers, conferences and seminars sponsored by the project, etc. While this aspect of project communication activities may best be handled by the ministry of health information office, very close supervision by the NCDD project is essential.

- Integration of ORT messages into existing media programs. Each radio or television station has its own health programs as well as other much more popular programs. Both may be used to diffuse ORT messages. The press also has different health and family sections which typically discuss different health issues. The first order of business should be to educate reporters and producers about Oral Rehydration and motivate them to address the subject matter in their programs. Second, detailed arrangements should be made with selected programs, within a general framework, to integrate ORT into the subjects addressed in these programs. Different approaches will be required for the health and the general / popular programs. This aspect of the program communication effort must be undertaken directly by the project with the media personnel involved. The project should provide the content, approach, and means to pretest the material and evaluate its impact, the production being left to the media people as their responsibility in close coordination with the project. It should be mentioned here that as the audience of the specialized health programs, sections, and magazines is relatively much smaller, and is of a particular quality, emphasis should be more on popular programs and less on health programs, sections, or publications.

- Specially-produced programs. The project should start negotiations with one or two radio stations and make arrangements to produce and broadcast “Al Om Al Waaia” (The Aware Mother) program nationally. The program should be put on the radio during the peak of the diarrhea season, and should include competitions and prizes for listeners who follow the program regularly and can answer specific questions on the subject matter. The program would be publicized intensively through spot announcements few times a day which should be inserted before or immediately after other programs that are most popular among the target audience. While the same may be done on television, the cost could be prohibitive. An ideal arrangement would involve rerunning the program on additional radio stations, but such an arrangement may be quite difficult. For literate audiences, the same idea can be implemented, where print supplements or sections may be edited in direct cooperation with the project. While the NCDD project should subsidize the production of such programs or press sections, it should not by any means waste the project funds on buying newspaper space or radio air time for these specially produced programs. They are not to be confused with advertising.

- Social Marketing. By far, this will prove to be the most effective activity in reaching the target audience, different, but small segments of which are reached through the other communication campaign elements outlined above. Since the project does not have the means to produce communication material, this activity will have to be accomplished through the cooperation of three parties. First, the NCDD project must assume overall responsibility. Content development, pretest of ideas and of material at different stages of the production, approval of scripts and storyboards and evaluation of effect are typical NCDD project responsibilities. Second, radio and television officials should be involved at different stages, such that a sense of involvement develops among them, which would make the broadcasting of project messages more possible. These people or some of them at least, have good judgments of what does or does not work. Third, the actual filming and production should be contracted out to one or more of the public or private agencies specialized in quality production of audio, video, or print material. Such contractors, however, will have to be closely coached by the project, mainly because almost all possible contractors have little, if any, experience in social marketing communication, and have little experience in communication with the kind of audience the project seeks to reach.

V. Pretest, Evaluation, and Monitoring.

Two types of pretest of campaign material are advised, of course in addition to pretest among in-house experts. First, a pretest must be done with key experts in the technique being used (e.g., audio, video, photography, drama, etc.) Second, all material must be pretested among relatively small samples of the target audience. Both types of pretest may be repeated at different stages of the production. The NCDD project should assume the primary responsibility for pretesting.

Monitoring techniques will vary according to the kind of communication activity. For example, while the ministry of health information office could be responsible for sending copies of each of the news releases it manages to get printed on behalf of the project; other activities may require the specific attention of one or more persons on the NCDD project staff. Detailed monitoring schemes should be devised in conjunction with each activity.

Evaluation, both of the process and the impact should be undertaken both by the project itself and by outside contractors. Evaluation reports submitted by contractors on the project’s request may not substitute for the project conducting its own evaluations of different communication activities.

The Pilot Campaign

This three months pilot campaign was launched in Alexandria between August and October of 1983. The campaign relied heavily on radio, where a new show in the local Alexandria radio station devoted a daily 15-minute program for ORT. This “Aware Mother” (Al Om Al Waaia)radio program differed from typical health programs on Egyptian radio stations in at least two ways. First, the program employed different popular formats, especially drama, songs, prize competitions, and interviews with mothers. Second, the program and its material were based on audience research and included pretests of materials before broadcast.

In addition to radio, the campaign included the use of billboards, posters, stickers, flyers, as well as interpersonal communication, where a well known movie and TV star, Fouad El Mohandis, along with eminent pediatricians held ten rallies in selected sites all over Alexandria. The campaign also included the promotion of ORS in all Alexandria pharmacies.

The main messages in this pilot campaign focused on introducing the concept of dehydration, explaining its signs and seriousness, importance of continued nutrition and breastfeeding during diarrhea episodes, giving plenty of liquids, and taking the child to a hospital or health center to be given ORS, since ORS packets were not sufficiently available for home-use at that point. The campaign did not discuss mixing of ORS, since the NCDDP was in the process of changing the packet size from the then existing 27.5 grams to a smaller 5.5 gram packet. Furthermore, the project needed time in order to supply health centers all over the country with ORS packets, to avoid any shortages when demand is increased as a result of the campaign.

Fouad El Mohandis was the celebrity in the public rallies in Alexandria, as per the contract that NCDDP had concluded with an advertising agency right before I joined the project. He did quite well in the rallies, despite the fact that the agency was much disorganized and didn’t handle the events well enough. In one instance at the beginning of the rallies, he actually fainted and was almost suffocated by the crowds, because the agency under-estimated the size of the crowds that he would attract. Even though it was their job, I had to step in and request that he would be on an elevated stage rather than being on the same ground level with the crowds. Since the agency had no plans to build a stage. To save the day, I moved him to a first floor balcony where he could speak to the crowds who gathered right outside the building.

Television was a part of the pilot campaign, but was not used until the last week of January 1984, when a two-week TV campaign was launched, using three TV spots featuring the same celebrity, Fouad El Mohandis. This part of the pilot campaign had to lag behind the other communication components because using TV meant going national, since Alexandria did not have a local television station at that time.

This pilot TV campaign too did not include messages on the mixing of ORS, but focused instead on encouraging parents to take their children to health centers or hospitals. The reason was that the smaller packets of ORS had not yet been produced or made sufficiently available for home use. The campaign, however, emphasized the seriousness of dehydration, showed its signs, and stressed the need to continue feeding during diarrhea episodes.

Even though the contract with the advertising agency was approved by the ministry of health officials in August 1983, they suddenly became quite adamant in refusing to approve the appearance of Fouad El Mohandis in the spots. Their excuse was that he was an actor, and even worse, from their point of view, a comedian! We had to eventually make a compromise with them such that he would be introduced in the spot by a well-known pediatrician, Dr. Gameel Wali, who states in the beginning of the spot that he had explained the subject of dehydration to this well liked actor who would in turn rephrase that explanation in his own words! Those were the early days of using TV spots for health promotion, and the concept of using actors, let alone comedians to spread such messages was virtually unknown.

Following is a translation of the sound track of that very first TV spot in the campaign, which can be viewed here: https://youtu.be/7IW40sBu3OE

Dr. Gameel Waly, Pediatrician:

“Mr. Fouad El-Mohandis asked me about the dangers of dehydration (gafaf) that threatens our children nowadays. After I explained the subject to him, we will listen now to how he explains the dangers of dehydration in his nice way.”

Fouad El-Mohandis:

“Good evening to you, mother of the little one.

I have a few words for you

And my aim is for you to take care

And keep your eyes on your beloved baby

I want to speak with you about the dangers of child dehydration

Dehydration is caused by watery diarrhea or gastroenteritis

It makes the child, God forbid, like a squeezed orange or dried out sugar cane

His eyes are withered and sunken

His skin is dry

Always thirsty, weak and lethargic

These are the signs of dehydration that is caused by diarrhea

So what is the solution?

The solution is the oral rehydration solution!

This solution compensates the child for all the liquids he lost

And in a very short time

The child shines and becomes healthy again

Oral Rehydration Solution is available at hospitals,

Health units

And pharmacies

Therefore

The solution is in the solution

And the solution is the solution!

The pilot campaign conveyed “the following basic messages: (1) Give plenty of liquids (especially soups and juices) and continue breastfeeding your child if he/she has diarrhea; (2) Watery diarrhea and gastro-enteritis cause dehydration which can lead to death of the child; (3) Recognize the signs of dehydration: weakness, vomiting, high temperature, loss of appetite, and sunken eyes; (4) Take your child immediately to a hospital which has a special unit to treat dehydration if you recognize any of the signs of dehydration; (5) Continue to feed your child if he/she has diarrhea; and (6) Advantages of ORS, where to obtain it, and illustration of its impact.”[7]

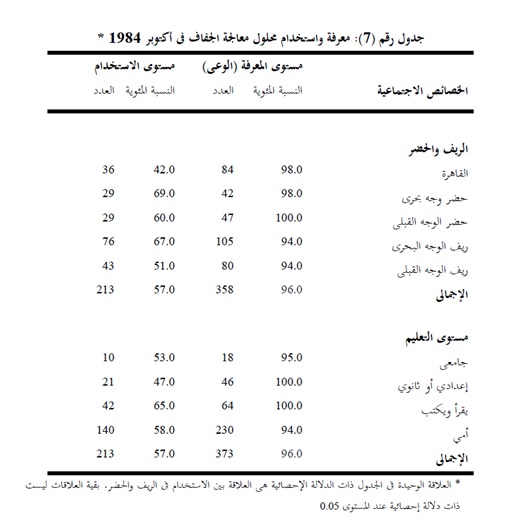

In May 1983 and before any communication effort was undertaken by NCDDP, a baseline survey of 2100 mothers was conducted in Alexandria. In December 1983, after the pilot campaign, but before the TV spots were aired, another survey of 525 mothers was also conducted in Alexandria. A third survey took place in March 1984, soon after the pilot TV campaign was launched. In all three surveys, key indicators of oral rehydration therapy (ORT), which includes giving ORS, continued feeding, giving liquids, and breastfeeding during diarrhea episodes, were measured, and a comparison of the results was crucial in shaping the project’s communication strategy and plans for years to come. Following are these key indicators[8] which have confirmed the validity and usefulness of the revised communication strategy and the theoretical framework which has been discussed earlier.

Table (1) Knowledge and Practice of Oral Rehydration Therapy in Alexandria 1983-1984

| Knowledge/Behavior Indicator | May 1983 | December 1983 | March 1984 |

| Knowledge: When to give ORS | 1.5 | 12.4 | 51.4 |

| Knowledge to continue breastfeeding | 3.0 | 21.7 | 64.6 |

| Knowledge to continue feeding | 6.1 | 30.5 | 41.1 |

| Knowledge to give liquids | 27.1 | 57.5 | 68.9 |

| Knowledge to visit doctor/hospital | 33.4 | 94.7 | 93.1 |

| Behavior: Ever use of ORS | — | 1.0 | 36.2 |

While the three months pilot campaign, without television, had a good impact on the knowledge of target mothers, television spots which ran for only two weeks had even a greater impact, particularly on “how to use” ORS and on behavior. The first lesson learnt from the pilot campaign, therefore, was the confirmation of the revised strategy premise that television would be more effective than any other media. As mentioned before, television viewership in Egypt had reached over 90% of the mothers in 1984.[9]

The National Campaign:

A series of focus group discussions were conducted on samples of target mothers and also on physicians revealed the need to make another strategic change. We found that while mothers liked the pilot campaign star, Fouad El Mohandis, but also discovered that a sizable minority of physicians were critical of him, not because he said anything medically wrong, but because he was a “Comedian”! Even though mothers, the primary target audience, were pleased with him, we thought it was best to identify another “spokesperson” that would enjoy a more popular liking. The person identified through focus group studies was Karima Mukhtar, a movie and soap opera star who usually plays the role of a good loving mother. This choice has proved to be an excellent one for the campaign, except that she was reluctant to appear on TV commercials which she had not done before. I was fortunate that Moaatz, her son was a student of mine at Cairo University. He helped me convince her that this campaign was going to be good for her name, which turned out to be very true. She in fact succeeded in making the Egyptian audience trust her advice to the extent that many women would ask pharmacists to sell them Mrs. Karima’s packet “Bako el Set Karima” instead of saying the official name for the ORS packet.

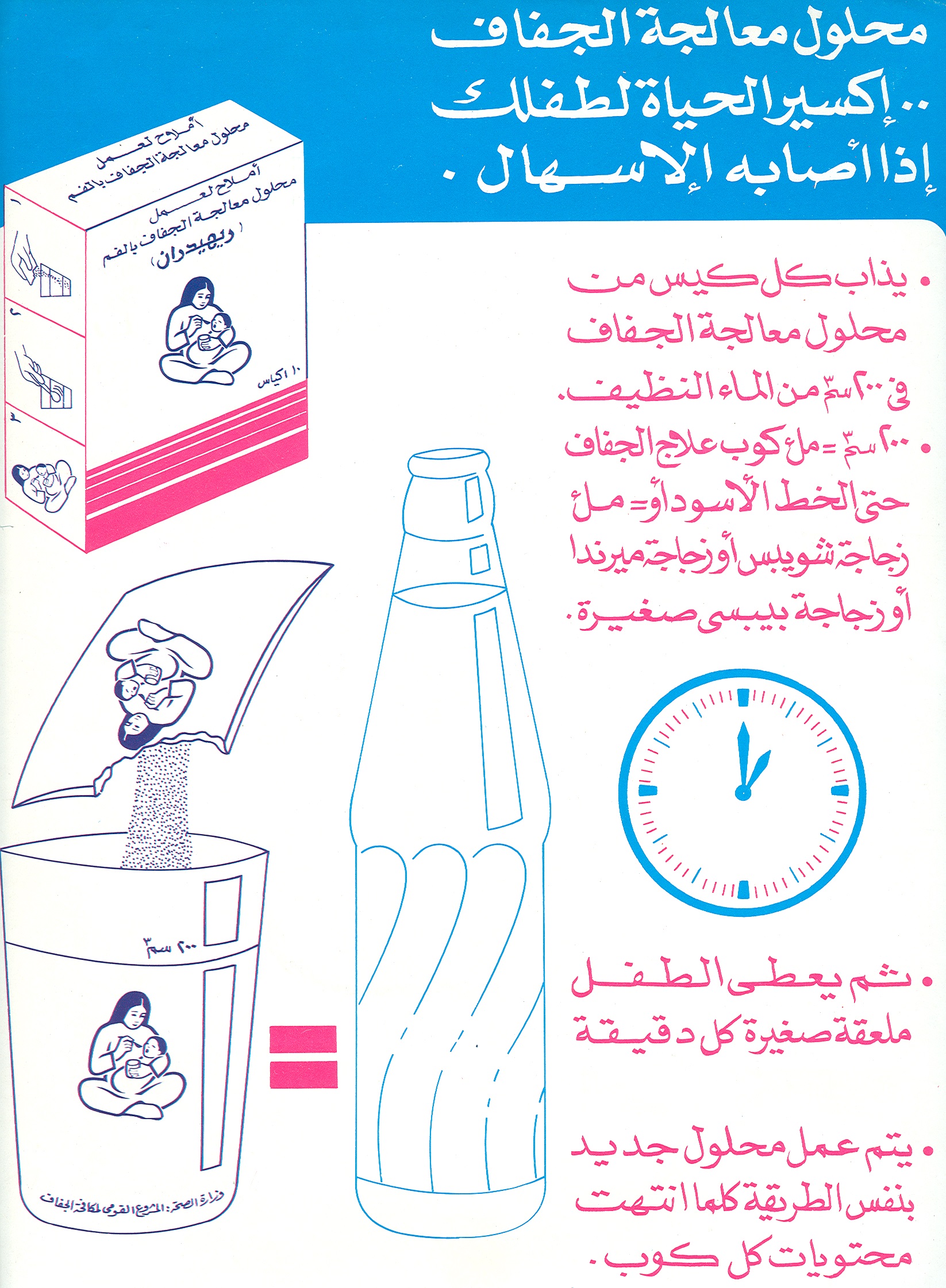

Karima Mukhtar appeared in the national TV campaign that was launched in September 1984, after the smaller ORS packets had been produced and distributed to virtually all health centers and pharmacies in Egypt. In addition to key messages from the pilot campaign, this national one introduced the new product and included instructions on its proper mixing and management. It also included one television spot on the prevention of diarrhea. Having had the confirmation from the pilot campaign that television was the most appropriate public information channel in Egypt for the target mothers, most of whom are illiterate but own TV sets, this medium received more attention in the plan than others, and most of the budget was allocated to production and airing of TV spots. On the other hand, a small portion of the budget was allocated to other media. The sound track of the TV spots was used to air the spots on the radio. Additionally, one hundred 3 by 5 meter billboards were placed in key locations near major rehydration centers all over the country, and a poster was placed in most pharmacies and health centers.

Karima Mukhtar was replaced after two years with other talents including actors, singers, folk musicians, as well as ordinary parents and healthcare providers who provided testimonials that helped consolidate the campaign impact on knowledge and attitudes. This is a link to all TV spots (59) that have been produced and aired between 1983 and 1989: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLxwmH-xqgi_ev7qMgEEiGxf0XbKBv5fV3

Knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys

National surveys[10] were conducted annually at the end of each diarrhoea season in a randomly chosen 1,100-household subset of the cluster samples and 400 households selected from low income clusters in Cairo. The study conducted after this first national campaign yielded very encouraging results, since it showed knowledge of ORS to have reached over 90 percent of mothers. Actual use of ORS after the campaign jumped to over 60 percent.[11] A series of annual campaigns followed this one. At the end of each campaign, both survey and focus group studies were conducted, which served to identify the campaign impact as well as new needs for additional messages.

The objective of the second campaign was to move beyond creating awareness of the danger of dehydration and the importance of oral rehydration, to teaching mothers specific skills, such as the use and management of ORS, proper nutrition, and the importance giving fluids during diarrhea. The third campaign was characterized by the appearance of real mothers and fathers in television messages. This series of commercials served to reinforce the information introduced in the previous campaigns especially that related to the administration of ORS. The fourth campaign addressed basic issues that had previously been postponed, such as the management of breastfeeding, personal and domestic hygiene, correct weaning practices, immunization against measles, and proper food preparation and cleanliness.

The media campaign mainly addressed the mother, especially in rural and poor urban areas, and in fact featured real mothers from different socioeconomic backgrounds. In addition, the campaign also emphasized the role of the father, grandmothers, doctors and pharmacists. Even children were also addressed, as it is known that, in Egypt, older children often assume responsibility for younger siblings.

Healthcare Providers

Contrary to the simple belief that everyone in Egypt, particularly healthcare providers would be on board to support oral rehydration in order to save the thousands of children who die every day because of dehydration, most of the doctors and pharmacists were initially against ORS for various reasons. Some opposed it due to ignorance and others because of opposing vested interests. We could not afford alienating healthcare providers, but we also had to change their beliefs, attitudes, and practices. This was quite a thin robe to walk on!

The main cause of the problem was that oral rehydration therapy was introduced in the curricula of medical schools at Egyptian universities only since 1983, so the vast majority of Egyptian physicians had not been therefore taught the ORT protocol. What they were taught was to give intravenous therapy, which was in fact too expensive and not available except in limited urban areas.

Furthermore, physicians excessively prescribed antibiotics and anti-diarrheal medications, which were also expensive and useless in preventing child dehydration that was the actual killer of children with diarrhea. On the other hand, pharmacists had a vested interest in recommending and selling those expensive and useless drugs, because their profit margin was dramatically much higher than ORS which was so much cheaper. Some negative comments on ORS were raised by some members of the pharmacists’ syndicate, but an extreme case of opposition to the campaign was that of a popular pediatrician in the Cairo district of Shobra, who was a pioneer in using intravenous solutions to treat dehydration. After the ORS media campaign began, he fought it so hard that he would stand on the balcony of his clinic and use a megaphone to advise passersby against using ORS.

A main objective of the communication campaign therefore was to inform physicians and pharmacists of the medical revolution that had taken place after the recent invention of oral rehydration solution, and to explain to them the benefits of using it. Furthermore, they had to be made aware that other drugs which they often prescribed were often useless in most cases of diarrhea.

Among the materials that were produced for physicians and pharmacists in the national campaign was an education film featuring the head of the medical syndicate, Dr. Mamdouh Gabr, who was also prominent pediatrician and former minister of health, with the heads of pediatrics departments in the leading Egyptian universities. Other materials included slides, booklets, treatment charts, and other training materials that were used in training workshops for healthcare providers. Both the Medical Syndicate and the Egyptian Pediatrics Society published newspaper advertisements in support of ORS, upon our appeal for help.

But this was not all. A secret weapon was deployed in the campaign to overcome the reluctance of healthcare providers to prescribe or advocate ORS. We benefitted from the great credibility that our campaign star has with mothers to pressure doctors in an indirect but very effective way. In a TV spot we let her say one of the most, if not the most important sentences in the entire campaign. She says to her neighbor: “take your daughter to the doctor, and he will prescribe ORS.” This one sentence has put so much pressure on doctors, and pharmacists as they are also called “doctors” in Egypt. They had to prescribe ORS or face the possible accusation by mothers that they weren’t “good” doctors, given the fact that Karima Mukhtar had more credibility with mothers than the minister of health himself, as one leading ministry of health admitted to me. Doctors had to cooperate with the campaign messages as they certainly didn’t wish to appear less knowledgeable or less caring than Karima Mukhtar. This particular TV spot can be viewed here: https://youtu.be/TrJlChZVwKw.

The Dilemma of Cups and Bottles

Between 1984 and 1990, over 60 television spots were designed, produced, and aired. These spots covered various issues such as defining dehydration, its signs and seriousness, how to prevent and treat it with ORS, how to mix and administer ORS, feeding during and after a diarrhea episode, prevention of diarrhea, rational use of other drugs and correct weaning practices. Each one of the TV spots was developed on the basis of research conducted before and after each annual media campaign, and was subjected to pretest among samples of the target audience.

We faced a real challenge with regards to the message on proper mixing of the ORS solution. This was due to the fact that the packet of ORS powder had to be dissolved in exactly 200cc of water, as it could be useless if dissolved in more water, and may actually harm the child if it was dissolved in much less water. The NCDDP commissioned a study to investigate whether or not there was a standard cup or glass in all households which could be used to measure the right amount of water. Unfortunately, there was none. We were indeed sweating over this dilemma, when I found the answer by mere chance, as I was watching a commercial on TV for one kind of soft drinks. The commercial was making the point that it was more economical to buy the one liter bottle because it holds as much as five small bottles, but is sold for the price of only four. This is when I shouted the famous scream: “I found it!” Given the fact that small soft drink bottles were available everywhere in Egypt, the message to use an empty one to measure the 200cc water needed for the ORS to be mixed correctly and safely has proved to be an essential and perhaps a life-saving one. At a later stage, the project produced 200cc plastic cups that were made available in the ministry of health rehydration centers. They were also supposed to be given away by pharmacists with each box of ORS, but they weren’t. This was unfortunate because the majority of caretakers of children used ORS at home, not at the ministry of health facilities. The soft drink bottle remains the only reliable measure to date, in view of the fact that those plastic cups aren’t produced anymore.

Audience Segmentation and Media Planning

Television advertising has had several advantages over other traditional means of health education. Commercials are attractive, they reach the majority of the target population in seconds, and they are carefully worded such that precise use of words and expressions conveys a particular technical content. In addition, they are pretested to avoid any possible misunderstanding or unintended sub-messages, and they enable the program to place them during viewing times that are most suitable to the target audience. Since each television spot normally has one specific message, a particular spot can be aired more or less often than others, depending on the needs of the target audience. It can also be aired at particular times when specific segments of the population are known to be watching television. For example, we found out that different segments of the audience watched movies and series on TV differently as follows:[12]

Table (2): The Relationship between the Level of Education and Watching Movies and Series on TV

| Educational Level | Percent Watching Movies & Series |

| Illiterate | 66 |

| Read and Write | 55 |

| High school | 42 |

| College | 37 |

At the same time the distribution of diarrhea morbidity happens to have an almost identical pattern, where children of the less educated mothers have more diarrhea episodes. It made sense, therefore, to place the TV spots before television movies and series to reach the population segments that are most influenced by the problem.

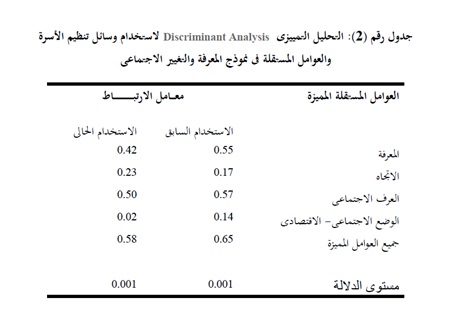

Contrary to results of many other social marketing programs, and to the “knowledge Gap Hypothesis”[13], the less educated segments of the Egyptian population adopted this new innovation (ORS) even faster than the better educated groups, as illustrated by these figures for ORS use after the 1983 and 1984 campaigns.[14] The principles behind this remarkable result are to be found both in the creative strategy and media planning as well as the theoretical framework of the “Knowledge and Social Change” model.[15]

Table (3) The Relationship between the Level of Education and Ever Use of ORS

| Educational Level | Percent Ever Used ORS |

| Illiterate | 57.6 |

| Read and Write | 64.6 |

| High school | 46.7 |

| College | 52.6 |

In addition to factors mentioned above, and to the very low and affordable price of ORS, this pattern of media effects was achieved because language used in the TV spots was very simple, and included actual words and expressions used by average mothers, messages were short and focused which made comprehension easy regardless of the educational level, message formats were appealing to all levels of the target audience, especially the lower-status segments. Finally, television spots addressed the low status audiences with the same respect they addressed other segments, a pattern which is somewhat absent in direct doctor-patient communication in Egypt.

Message Appeals for Health Providers

The major appeal for physicians, pharmacists and nurses was that ORT is state-of-the-art medical care, or “the medical revolution of the 20th century.” This message was presented in print materials, seminars, educational videos. A booklet designed for physicians included the following statement on the cover page: “If the purpose of medicine is to save lives, what is the single most important discovery since the introduction of penicillin?” A second booklet for pharmacists used the same appeal and included the same statement. The same concept was used in a scientific film for physicians entitled “Scientific Breakthroughs in the Treatment of Acute Infantile Diarrhea”. Furthermore, the information provided in the booklet for physicians was translated into visuals, using a slide set which showed pictures of the same child before and after taking ORS. Physicians were able to see a demonstration of what ORS could do in a span of only four hours.

Messages to nurses used a different appeal. Building on their characterization as “angels of mercy”, these messages appealed to their humanitarian orientation and image to promote ORS to save the lives of little children. For example, a booklet for nurses had this statement on its cover: “people often go to the angel of mercy for a precious advice. Help save the lives of children who have diarrhea by advising mothers to give ORS.”

Messages Appeals for Mothers

Since 1984, the campaign for mothers has used a mixture of emotion and information. While it was very tempting to use a fear appeal, since the subject matter literally involves life and death, it was decided that a fear appeal would hinder the learning process. The priority was to provide mothers with the essential information which they need to care for their children, including how to prevent diarrhea and dehydration, how to prepare ORS, and how to feed and wean their children correctly. A major assumption we made in planning the campaign was that mothers would act upon such information once they understood it. The overall appeal has been mothers’ love and caring for their children. Karima Mukhtar was selected to play the leading role in the 1984 and 1985 media campaigns has personalized the loving mother appeal quite effectively. Other celebrities whom we employed in subsequent campaigns followed the same pattern.

However a small dose of fear appeal was used lightly and selectively in contexts where resulting anxiety is immediately relieved in the same message. For example, one TV spot shows a woman who is frightened by dehydration, but the loving, experienced mother comforts her by saying that while dehydration could be fatal, it can be overcome and even prevented by giving the child ORS and liquids. A second TV spot showed the signs of dehydration but stated that it is preventable and happens only if the child is neglected and not given ORS. Messages emphasized that all mothers are capable of saving the lives of their children.

Campaign messages were all developed on the basis of research results. Expressions used in the TV spots to describe dehydration, diarrhea, the signs of dehydration and the way the child looks when he/she is ill and when he/she recovers, etc., were all taken from actual expressions used by mothers throughout Egypt. Furthermore, the content of the message also responded to research results. For example, the first three campaigns defined dehydration in terms of its signs (sunken eyes, dried out skin, weakness, etc.) While such tangible evidences of dehydration helped illustrate what dehydration “does”, they stopped short of explaining clearly what it is. Subsequent campaigns made the concept clearer through making analogies between a dehydrated child and a plant which was dried out because it was not watered. Another spot compared two children, one who took ORS and another who did not, to two flowers, one that looked so fresh because it was kept in water and another which became dried out because it was not. This shift in the presentation of dehydration from “what it does” to “what it is” came as a direct response to results of evaluation research which found that while mothers could state the signs of dehydration, they did not quite understand the concept well enough.

Can the Egyptian experience be replicated?

Characteristics of the Egyptian society, culture, and media system may resemble or differ from those of other countries experiencing similar problems related to ORT. For example, Egypt is extremely fortunate in that more than 90 percent of its population at the time the campaign started had regular access to television and more than 95 percent owned radio sets. With these same resources, however, many public education campaigns did not succeed in Egypt. While such resources are a great asset, how the ORT campaign used them was the primary contributing factor towards achieving the campaign results. In global terms, this is fortunate because it means that the Egyptian ORT program’s achievements can be replicated in other health issues and in other countries, as long as the same principles regarding media usage are followed. Some of the most important factors in planning and implementing this successful Egyptian campaign follow[16].

- The campaign implemented a carefully designed communication strategy that included the use of the mass media, training, and market research. There was a clear theoretical framework and methodology that guided every step of the way for inducing the desired knowledge and behavioral change.

- Culturally relevant use of the media was of central concern. Every culture has its own patterns of communication, preferred artistic tastes, formats, idols, etc. Characteristics of the Egyptian culture were closely observed in the design and production of the media messages. For example, when Karima Mukhtar, a motherly, well-liked and respected actress was chosen to star in the TV campaign, the vocabulary she used, the way she dressed, and the accompanying visuals all helped the audience identify with her and heed her advice.

- The program was successful in integrating the sociological and anthropological research findings into the creative development of the media messages. This input was made both before scriptwriting and at different stages where materials were pretested for technical accuracy and cultural relevance. Artists, producers, and other media talent aren’t normally used to such a methodology, so this was overcome by thorough supervision of all aspects of the media productions.

- The campaign was successful in securing the consent of medical authorities on the technical content of messages. The project could have bogged down in differences of opinion on the technical details. Considerable attention and effort were given to reconciling these differences of opinion and arriving at technically correct messages that were accepted by different medical authorities. No messages were presented without this technical review and approval.

- The mass media campaign was constantly coordinated with other elements of the program. For example, it was important that all research findings be carefully processed for their relevance to the media campaign. The presentation of mass media messages also had to be coordinated with the production and the actual availability of ORS in the health facilities and pharmacies, in order to avoid creating demand ahead of product availability. It was also essential to ensure that mass media messages are complemented with and supported by the content being provided in the training programs for healthcare providers.

Results and Impact on Mortality

Less than two years after the first national campaign was launched, the British Medical Journal wrote that “the lives of more than 100,000 children have been saved in Egypt in what may be the most successful health education program”[17] Another year later, The 1986 annual State of the World’s Children by Unicef included a chapter with the title “Egypt: Leading the World on ORT”[18]

As mentioned earlier, the NCDD had conducted a baseline survey in the city of Alexandria in 1983, before launching the pilot campaign. The project was also keen to conduct annual national surveys in the following years for two vital reasons: (1) to evaluate the impact of the communication campaign for the corresponding year, and (2) to provide the research input required for planning the subsequent one. For this reason, the project contracted with Dr. Nahed Kamel[19] from Alexandria University to conduct the baseline survey in 1983, and contracted with Social Planning, Analysis and Administration Consultants (SPAAC)[20] to conduct these national surveys in 1984, 1985, 1986 and 1988.

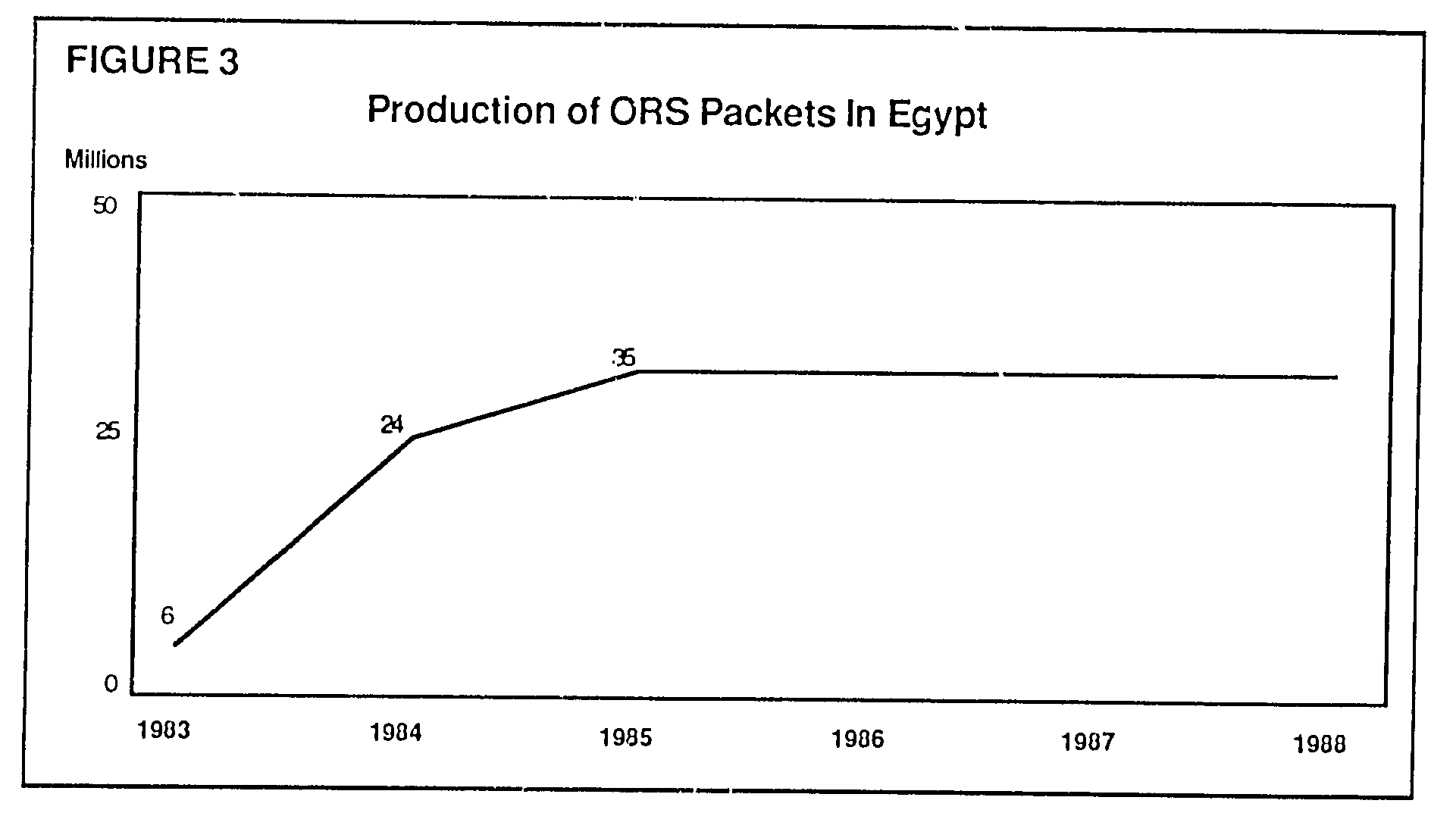

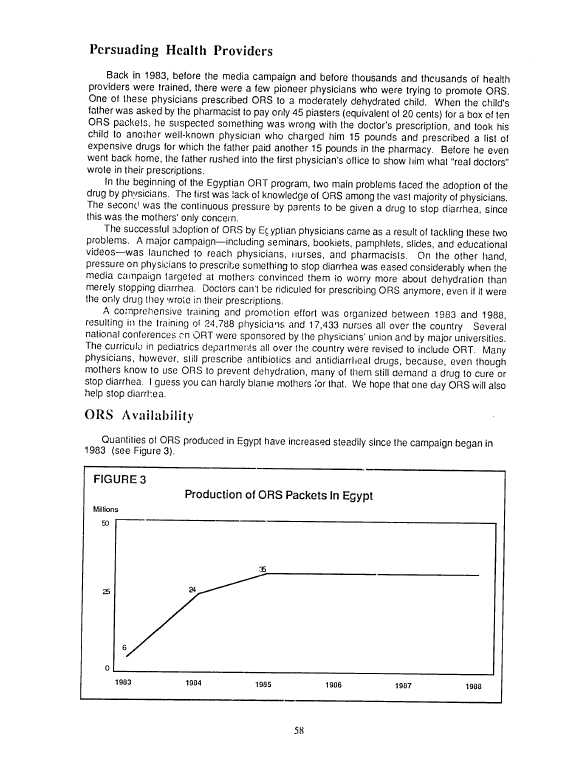

According to these surveys, knowledge and use of ORS have dramatically increased as a direct result of the communication campaigns between 1983 and 1988. While both knowledge and practice of oral rehydration were practically nonexistent in 1983(knowledge was 3% and use was 1.5%), the percentage of women who know of ORS increased to 94 percent in 1984 and to 98 percent in 1988. Use of ORS followed the same pattern in further confirmation of the validity of the model of “Knowledge and Social Change”[21] and jumped to 50 percent in 1984 and to 66 percent in 1988. Even more indicative of the power of television to teach a mass audience specific skills, the knowledge of correct ORS mixing has increased to 53% of those who knew ORS in 1984, and to 96 percent of all others who knew of ORS in 1988. The same results have been reported by M. El-Rafie and others.[22] These findings are presented in figure (5) below:

Impact on Infant and Child Mortality

Only 2 years after the project began, vital statistics and other data began to show the impact of this impressive increase in mothers’ knowledge and use of ORS. The British Medical Journal concluded in 1985 that “the lives of more than 100,000 children have been saved in Egypt in what may be the world’s most successful health education program”[23]. The journal also reported that “the project decided, in the face of opposition from doctors and others, to use the mass media to tell Egyptian people about oral rehydration treatment. Radio, television, and posters were used, and within 2 years 95% of Egyptian mothers knew about the treatment, 80% had used it to treat their child’s last episode of diarrhea and between 109,000 and 190,000 child deaths had been prevented. The campaign used actors, singers, comedians, doctors, drama, prizes, competitions, interviews with mothers, and for the first time messages were delivered in colloquial Egyptian rather than classical Arabic.”[24] The journal concluded that “the World Health organization has been so impressed with the results of the Egyptian campaign that it is encouraging other countries to adopt similar programs”[25].

The following year, a team of eight Egyptians and eleven international experts from the Ministry of Health, USAID, UNICEF, and the World Health Organization conducted a Project Review in June and July 1986. They wrote in their report that “consistent with findings of a number of studies reported by the project, the Review found impressive knowledge and use of ORT among mothers. Of 161 mothers interviewed during the review, 96% knew what a packet of ORS was used for, 82% said they used it and 71% knew some signs of dehydration. Of ORS users, 97% could correctly mix it”[26]. The review team also stated that “the greatly increased access to and knowledge of ORS have afforded mothers opportunities to prevent death due to dehydration in their children-an important accomplishment which has been achieved at a modest cost of a little more than one Egyptian pound for each mother gaining this benefit. It is also noteworthy that these impressive achievements have been largely made in the short time span of three and a half year. It is apparent that the above findings can be attributed in large part to a well planned and carefully implemented mass media campaign very largely channeled through television”[27]. This report also refers to another important result of the television campaign: “the project’s wise focus on the primary target audience, mothers, has resulted in creating a demand-driven system which has important positive implications for the sustainability of the project’s achievements”[28].

Upon the project completion in 1989, the Lancet published a final report which stated that “packets of Oral Rehydration Salts are now widely accessible; oral rehydration therapy is used correctly in most episodes of diarrhea; most mothers continue to feed infants and children during the child’s illness; and most physicians prescribe oral rehydration therapy. These changes in the management of acute diarrhea are associated with a sharp decrease in mortality from diarrhea, while death from other causes remains nearly constant”[29]. The report documents the impact on mortality on the basis of census data and vital statistics: “infant mortality rate due to diarrhea declined from 29.1 in 1983 to 12.3 in 1987, while non-diarrheal infant mortality rate declined during the same period by a very small fraction, from 35.6 in 1983 to 32.8 in 1987[30]. Furthermore, childhood mortality (for children aged 1-4 years) declined from 4.0 in 1983 to 2.3 in 1987 for diarrheal deaths, and from 6.0 in 1983 to 5.5 in 1987 for non-diarrheal deaths[31]. The following graph illustrates how diarrhea-related infant mortality rate declined much faster than non-diarrhea related mortality between 1983 and 1987.

It is easy to notice how the diarrhea related mortality rate has changed quite considerably during the life of the campaign, while the change in non-diarrheal mortality was minimal. The decline in diarrhea-related mortality is almost identical with the change in knowledge and use of ORS, which is shown earlier in figure (5), which suggests that these remarkable declines in mortality have been a direct result of increased knowledge and use of ORS, breastfeeding and giving liquids during diarrhea, which were the primary messages of the media campaign. This is perhaps the reason why Ruth Levine has concluded that “the most pivotal component of the program was the social marketing and mass media campaign.”[32]

An argument could perhaps be made that infant mortality had been on the decline before the campaign, and that what was reported as an impact during 1983-1989 is no less than a continuation of that trend. The following graph which was presented by El-Rafie and others has definitive answer to this possible argument. The graph shows the proportion of annual infant deaths during the peak diarrhea season (May to August), and illustrates how it stayed above 45% since 1970 until the end of 1983, after which it declined sharply. “More than half of the seasonality of mortality noted in 1983 had disappeared by 1987.”[33]

In absolute numbers, Levine estimates that “because of the reduction in diarrheal deaths between 1982 and 1989, 300,000 fewer children died.[34]

In even more precise figures, Peter Miller and Norbert Hirschhorn calculate that 316,612 children have been saved in Egypt between 1982 and 1989, of whom 202,113 are infants and 114,499 are children between the ages of 1 and 4.[35] They made these calculations as follows: for infant mortality, calculations based on registered births and infant diarrheal deaths; for children 1-4, calculations were based on official CAPMAS estimates of children aged 1-4 and on registered diarrhea deaths for those ages.[36]

It is reasonable to expect that many more hundreds of thousands of lives would be saved after 1989, as a result of this project and the media campaign. New epidemiological and demographic studies, as well as subsequent records of vital statistics and census data should carry the answer to this question. The campaign came to a halt after 1989 because funding of the project from USAID has reached its planned end. It goes without saying that various issues need not be neglected as a result, but in fact require a more sustained effort. This includes the prevention of diarrhea itself, better case management, improved diagnosis of dehydration and further reduction of unnecessary antibiotics and anti-diarrheal drugs also need.

While the effects of any communication campaign messages are not expected to be everlasting, however, findings of the Egyptian demographic and health surveys since the campaign ended are encouraging indeed. Towards the end of the project, the Egyptian Demographic and health Survey (EDHD) of 1988 reported that “almost all mothers of children under age 5 are aware of Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT).[37] Three years after the project ended, the EDHS 1992 reported that “virtually all mothers know about ORS packets and 70 percent say that they have used the packets at some time.”[38] In 1995, the EDHS found that 98.2 of mothers knew of the use of ORS packets for treatment of diarrhea.[39] Ten years after the project and campaign ended, the 2000 EDHS reported that: “virtually all mothers (98 percent) are aware of the availability of packets of oral rehydration salts that can be used to prevent dehydration.”[40]

These research findings provide further anticipation that empowering mothers with the necessary knowledge and skills to treat their children and to protect them from death due to dehydration has already constituted a medical revolution, and that mothers will continue to convey the skills that they have acquired to the next generation of mothers. The communication campaign to combat child dehydration has indeed left its mark on Egyptian society; a mark that time will never erase as long as the Nile flows through the land.

Video Resources:

This video (in English) is a documentary on NCDDP and the ORT campaign in Egypt.

This video (in Arabic) is a documentary on NCDDP and the ORT campaign in Egypt.

References

[1] Al-Ahram Newspaper, Cairo, Egypt, June 8, 1986, p. 13.

[2] The National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Project (NCDDP), Project Paper”, NCDDP, 1983.

[3] Farag Elkamel, Communication Strategy of the Egyptian ORT Communication Campaign, August 1983. https://www.academia.edu/41699754/Communication_Strategy_of_the_Egyptian_ORT_Communication_Campaign

[4] Ibid.

[5] Farag Elkamel, “Knowledge and Social Change: The Case of Family Planning”, the University of Chicago Department of Sociology, Ph.D. Dissertation, 1981.

[6] https://elkamel.wordpress.com/category/theory-methodology/

[7] Farag Elkamel and Norbert Hirshhorn, “Thirst for Information”, selected papers of the 1984 Annual Conference of the National Council for International Health, NCIH. June 11 – 13, 1984.

[8] Ibid.

[9] MEAG, “Evaluation of 1984 ORT campaigns”, Report submitted to NCDDP, Middle East Advisory Group, October 1984.

[10] El-Rafie, M. et. Al. Effect of diarrhoeal disease control on infant and childhood mortality in Egypt. The Lancet, Volume 335, Issue 8685, 10 February 1990, Pages 334-338

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] G. Donhue, P. Tichnor, and C. Olien, “Mass Media Effects and the Knowledge Gap”, COMMINCATION RESEARCH, 1975. (Vol. 2), pp. 3-23.

[14] MEAG, Op. Cit

[15] Farag Elkamel, “Knowledge and Social Change: The Case of Family Planning”, the University of Chicago Department of Sociology, Ph.D. Dissertation, 1981.

[16] Farag Elkamel, “How the Egypt ORT Communication Campaign Succeeded”. ICORT II Proceedings, Washington D.C. December 10 – 13, 1985.

[17] THE BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL, VOL. 291, 2 NOV. 1985

[18] Unicef, The State of the World’s Children, 1986. P.28

[19] Nahed M. Kamel, The Morbidity and Mass Media Survey, Final Report (Cairo, Egypt: NCDDP, 1984).

[20] SPAAC, Evaluation of NCDDP National Campaign (KAP of Mothers) (Cairo, Egypt: NCDDP). Four reports on national surveys in Egypt, 1984, 1985, 1986, and 1988.

[21] Farag Elkamel, “Knowledge and Social Change: The Case of Family Planning”, the University of Chicago Department of Sociology, Ph.D. Dissertation, 1981.

[22] El-Rafie, M. et. Al, ibid.

[23] The British Medical Journal, (Vol. 291), November 1985. P.1249

[24] Ibid

[25] Ibid

[26] Draft Report of the Second Joint Ministry of Health / USAID / UNICEF / WHO / Review of the National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Project (NCDDP) in Egypt, June 15 – July 13, 1986.

[27] ibid

[28] ibid

[29] El-Rafie, M. et. Al ibid.

[30] Ibid, table 2, p.335

[31] Ibid

[32] Ruth Levine, Case Studies in Global Health: Millions Saved. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2007, p.61

[33] El-Rafie, M. et. Al. Op. Cit., p. 336

[34] Ruth Levine, Op. Cit, p. 57

[35] Peter Miller & Norbert Hirschhorn. “The effect of a national control of diarrheal diseases program on mortality: The case of Egypt,” Social Science & Medicine, Elsevier, vol. 40(10) May1995. P. 24

[36] Ibid.

[37] EDHS 1988, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR14/FR14.pdf, p. xxxi

[38] EDHS 1992, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR35/SR35.pdf, p.16

[39] EDHS 1995, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR71/FR71.pdf, p. 176

[40] EDHS 2000, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR117/FR117.pdf, p. 157