Viral Hepatitis has been one of the world’s most pressing health problems. It affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide, causing acute and chronic liver disease and killing close to 1.5 million people every year, mostly from hepatitis B and C. These infections can be prevented, but most people don’t know how.

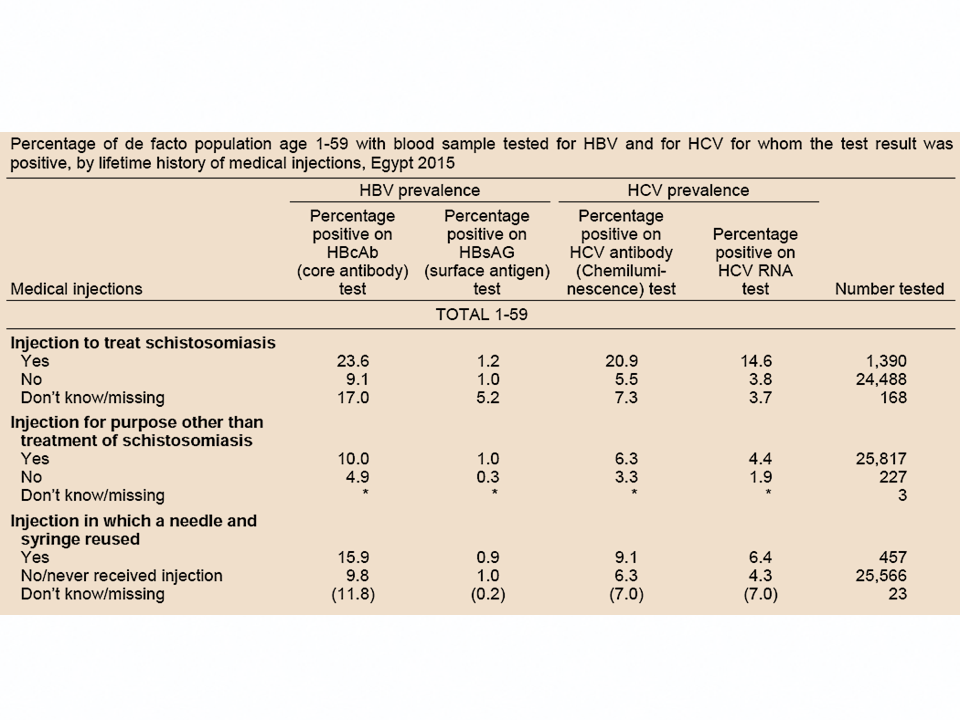

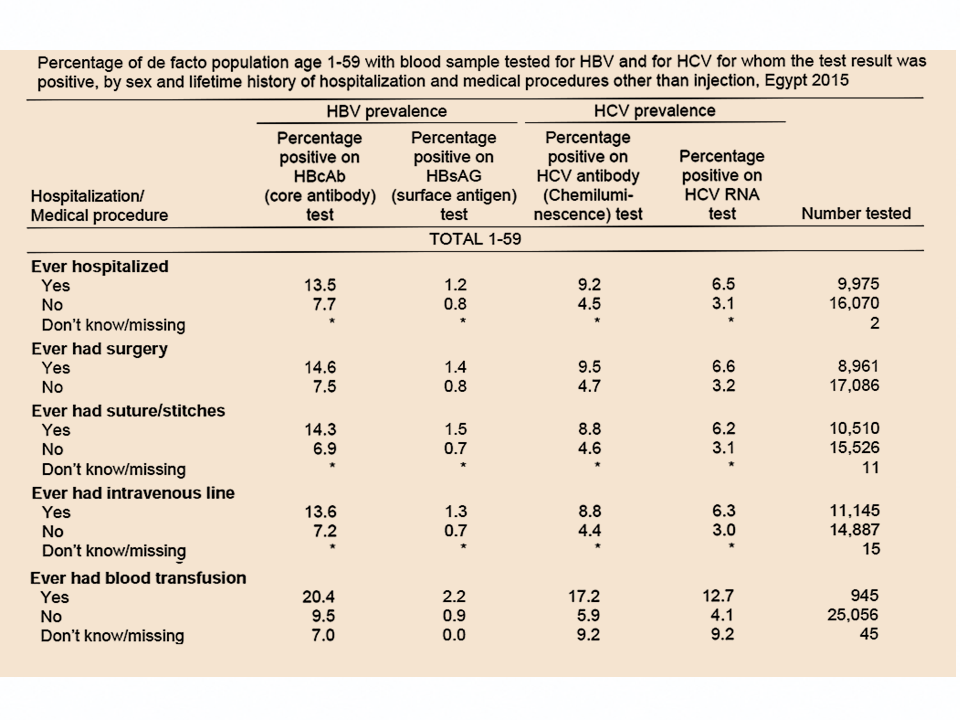

Many Egyptians have been infected with hepatitis C as a result of inadequately sterilized needles during mass campaigns to treat Schistosomiasis which started in 1960s and continued through the early 1980s. Afterwards, the virus continued to spread through infected blood and relevant items.

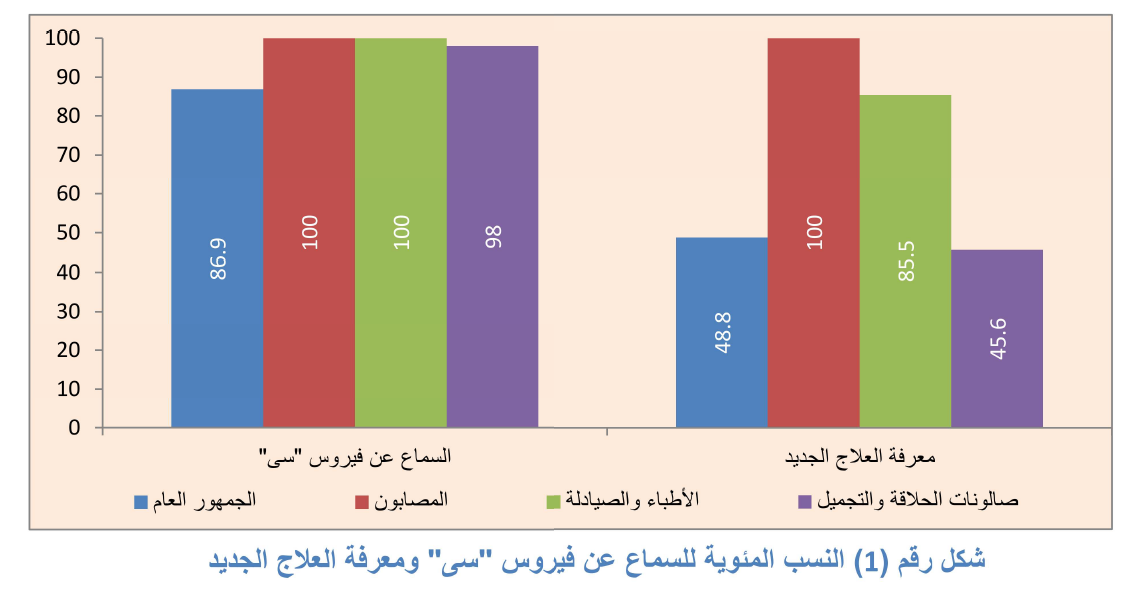

By 2014, Egypt had one of the highest global burdens of hepatitis C virus infections in the world. It was estimated then that 4.4% of the population 1-59 years old and 7% of the population between 15 and 59 years are chronically infected. A new national strategy needed to be developed and implemented by national and international parties to meet this major challenge.

As senior communication adviser to the World Health Organization (WHO) in Egypt between 2014 and 2016, I contributed the following:

- Wrote the Communication Plan for Hepatitis C Awareness and prevention.

- Supervised the development and production of a documentary film on the HCV problem in Egypt.

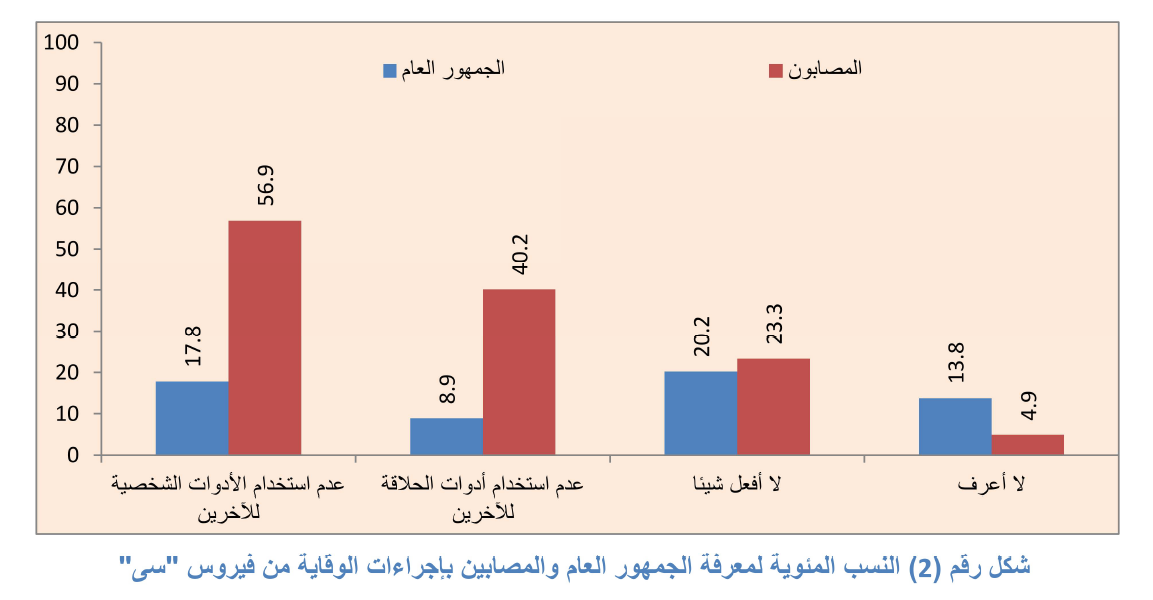

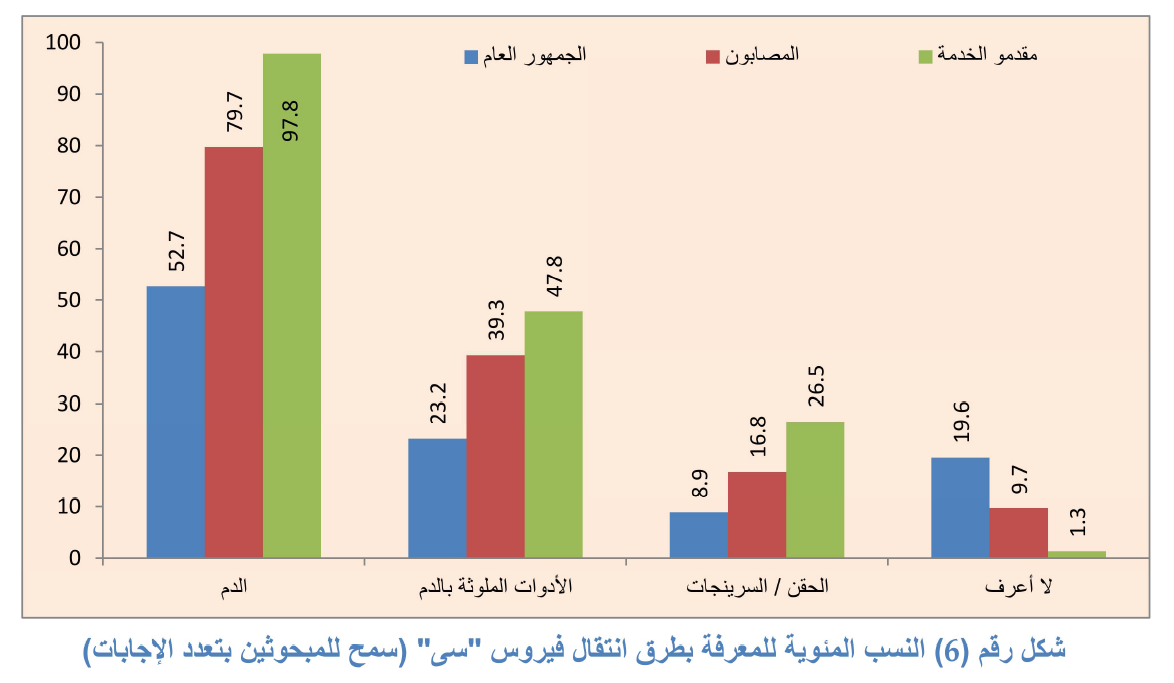

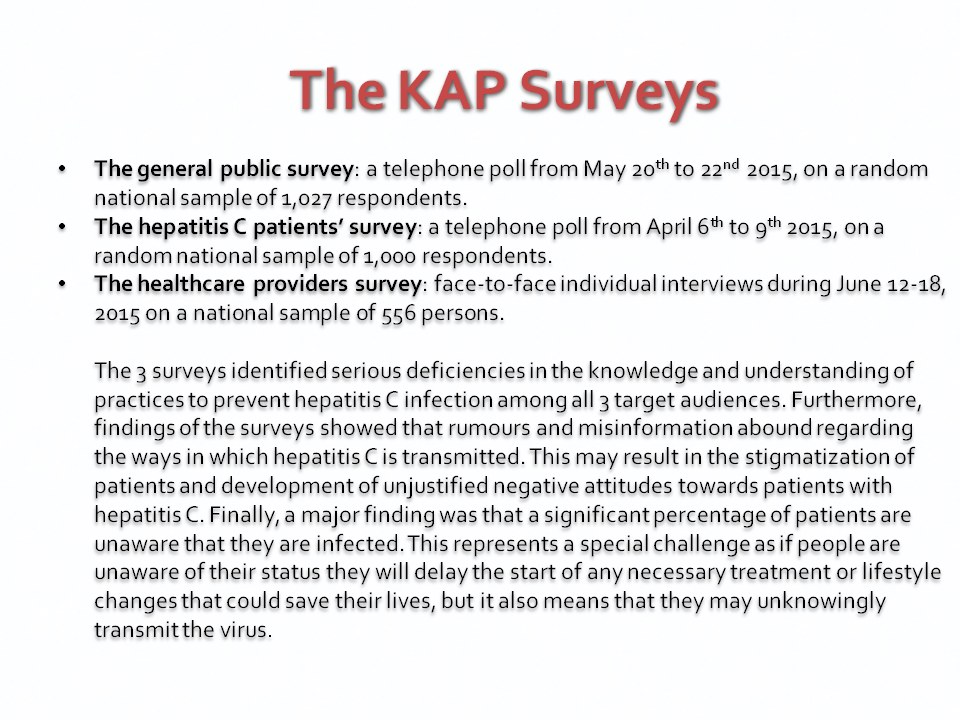

- Designed and supervised the implementation of three KAP surveys in Egypt during 2015 on: (1) the general public, (2) hepatitis C patients, and (3) healthcare providers.

- Analyzed the data from the three surveys and concluded recommendations for the media strategy, communication messages, targeting, and appropriate media selection.

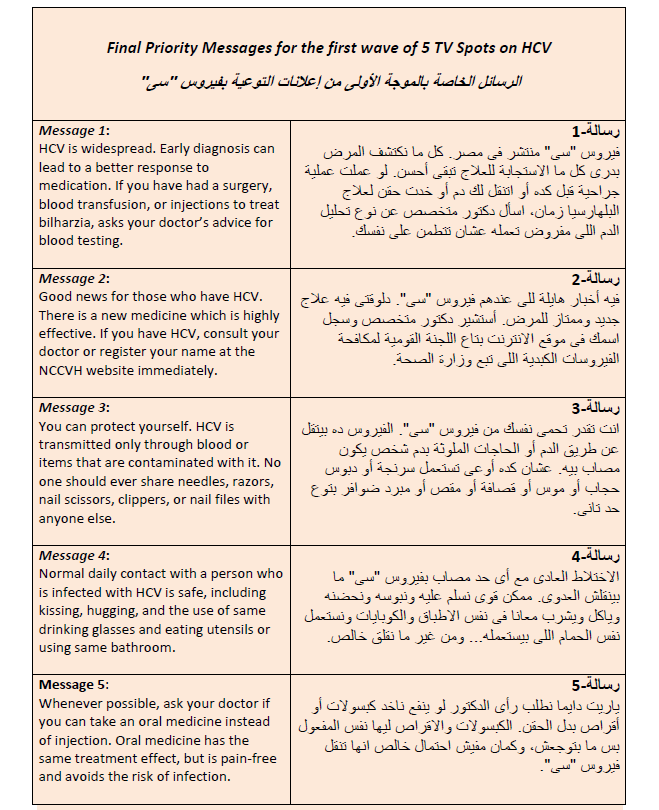

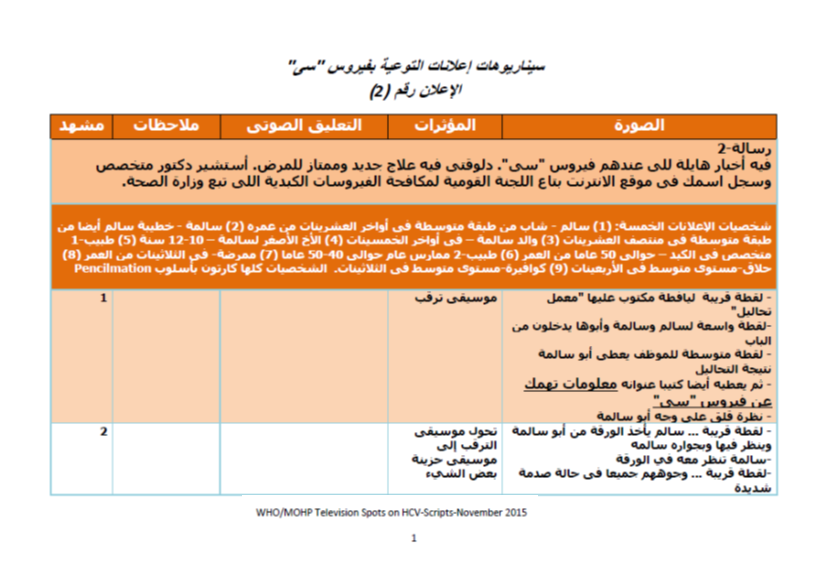

- Concluded the Priority Messages for the First Wave of Hepatitis C TV Spots in Egypt.

- Developed the first Egyptian national campaign on hepatitis C awareness and in 2016-2017, which included five television spots, a poster, and a pamphlet.

- The involvement of in the national effort to combat HCV continued after I left WHO, as I was nominated by Cairo University to help the Ministry of Health and Population as the senior communication adviser for the national drive to treat all infected persons in Egypt, which was launched in 2018 and continued for 7 months, from October 2018 to April 2019. As I recommended to the ministry, the campaign should never assume that the problem has completely disappeared. There is a very strong need to continue educating the public about prevention, alerting high risk groups to get a checkup, and upgrading the infection control knowledge, skills, and practices of healthcare providers. This is the link to this national drive: http://www.stophcv.eg/

The Communication Strategy & Plan for Hepatitis C Awareness and Prevention in Egypt

Overall Strategy Guidelines

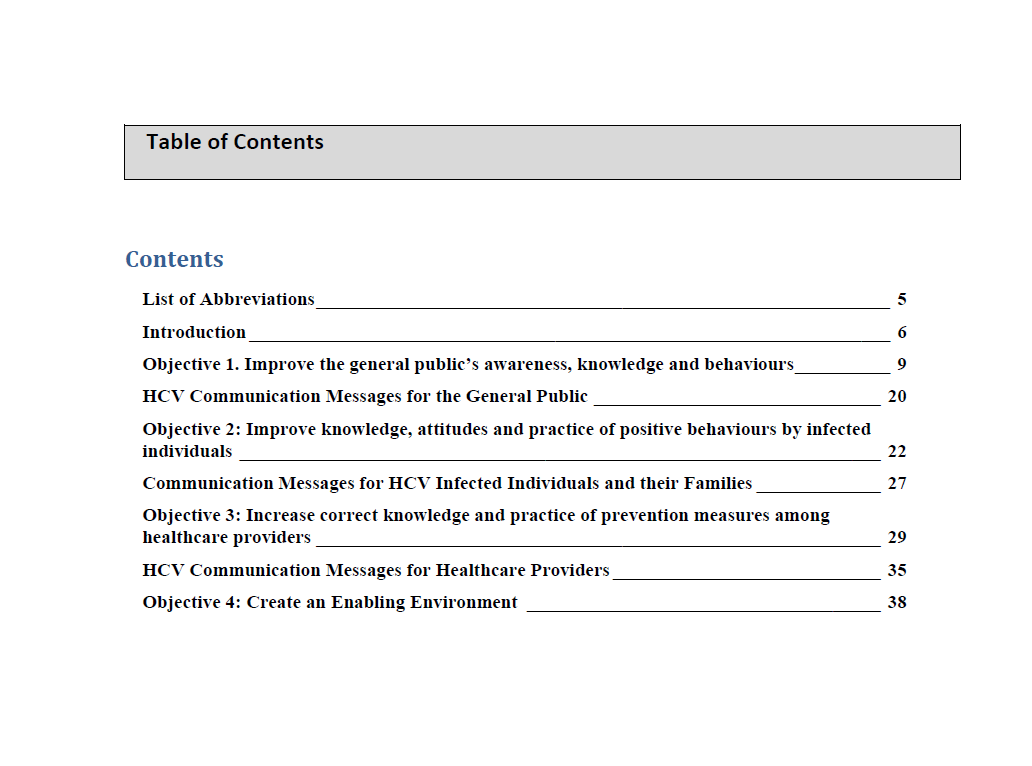

This implementation plan addresses the role that communication can play in the prevention of Viral Hepatitis in Egypt and describes the sequence of events that will result in the desired change. It also describes a logical progress from the broad goals to objectives, accomplishments or outcomes and then to very concrete actions and activities. The plan includes the following:

- Specific and measurable objectives, indicators, and activities within a specific time frame

- Defined action steps with accountability, deadlines and resources needed

- Links to the national Action Plan and to the Communication Strategy.

When put into use, this plan should be a dynamic tool. Target dates may need to be adapted, and actual results may be different than anticipated. This document is therefore a tool to document progress as well.

Because the implementation plan is detailed with specific activities, and since the resources needed may be beyond the capabilities of one single entity, partner organizations can choose to be responsible for sponsoring specific appropriate sections or activities, which are consistent with their organization’s strategic plans. Doing so will help to document their contributions to this collaborative endeavor and to track their efforts internally.

Another important use of this detailed implementation plan is its utility in process evaluation. When the campaign is evaluated, a thorough investigation must be undertaken to determine which activities have been implemented and which were not, and how the implementation itself took place. As this plan is approved, the country can move into actual implementation where partners would use it as a foundation for implementation, monitoring, evaluation, and coordination.

The Plan of Action for the Prevention, Care & Treatment of Viral Hepatitis, Egypt 2014-2018 is the main background document that constitutes the source of what is considered in this implementation plan as goals, objectives, performance measures or indicators, and activities.

Goal: In this implementation plan, the overall goal is to reduce or eliminate new infections of HCV and to encourage currently infected persons to seek immediate treatment.

Objectives:

- Improve the general public’s knowledge and Behaviors and their understanding of HCV, its seriousness, care, treatment, and prevention.

- Help eliminate stigmatizing people infected with HCV.

- Improve knowledge, attitudes and practice of positive behaviors of infected individuals and their family members regarding diet, exercise, medical follow-up, prevention, and seeking treatment.

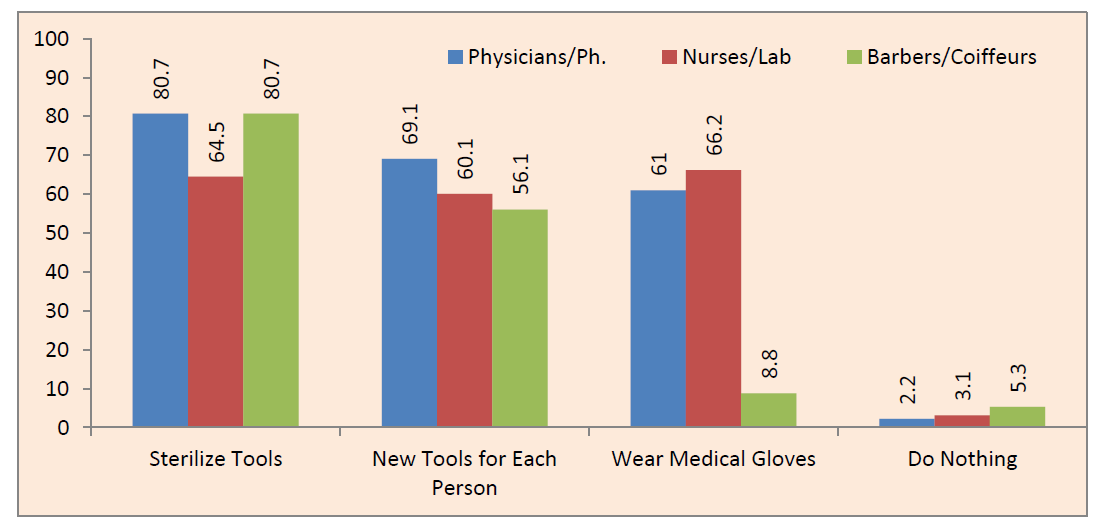

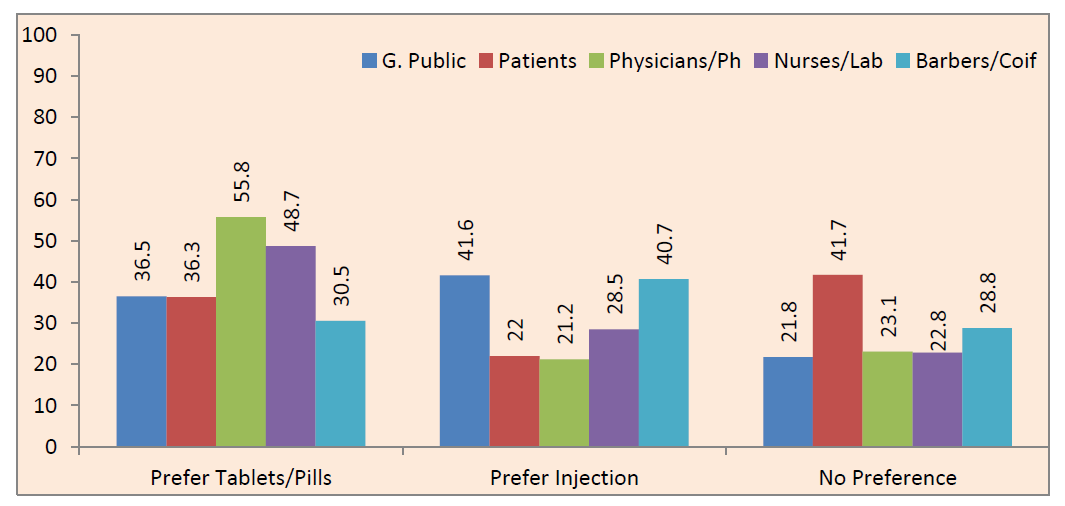

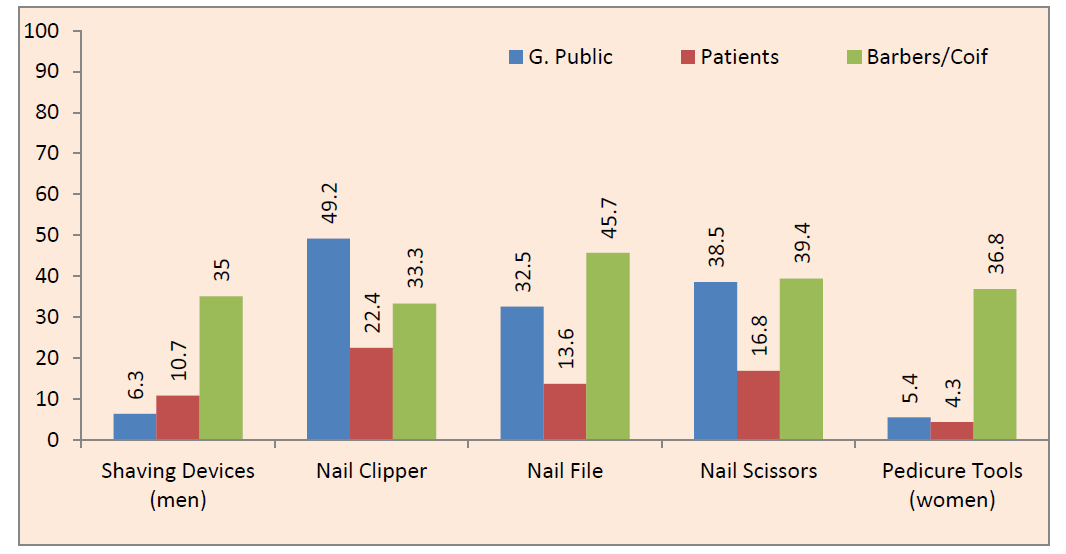

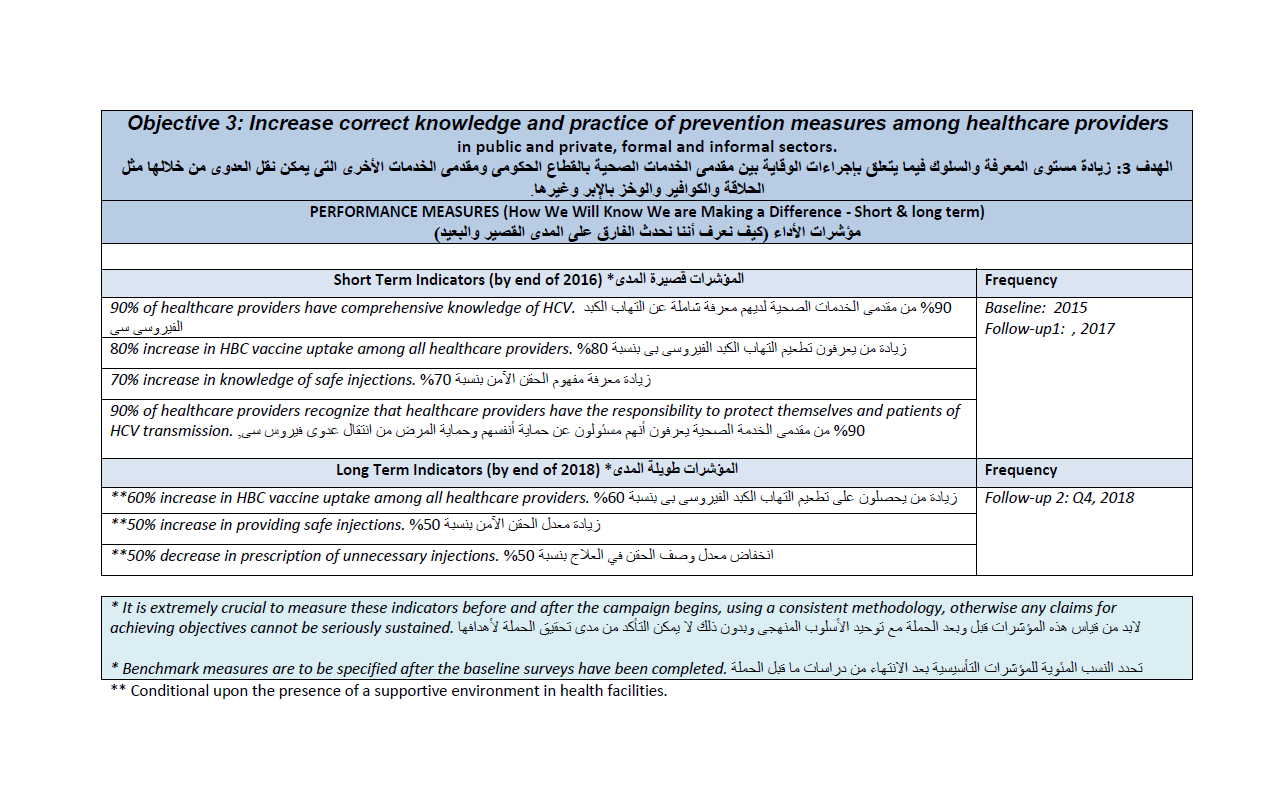

- Increase correct knowledge and practice of prevention measures among healthcare providers, in public and private, formal and informal sectors.

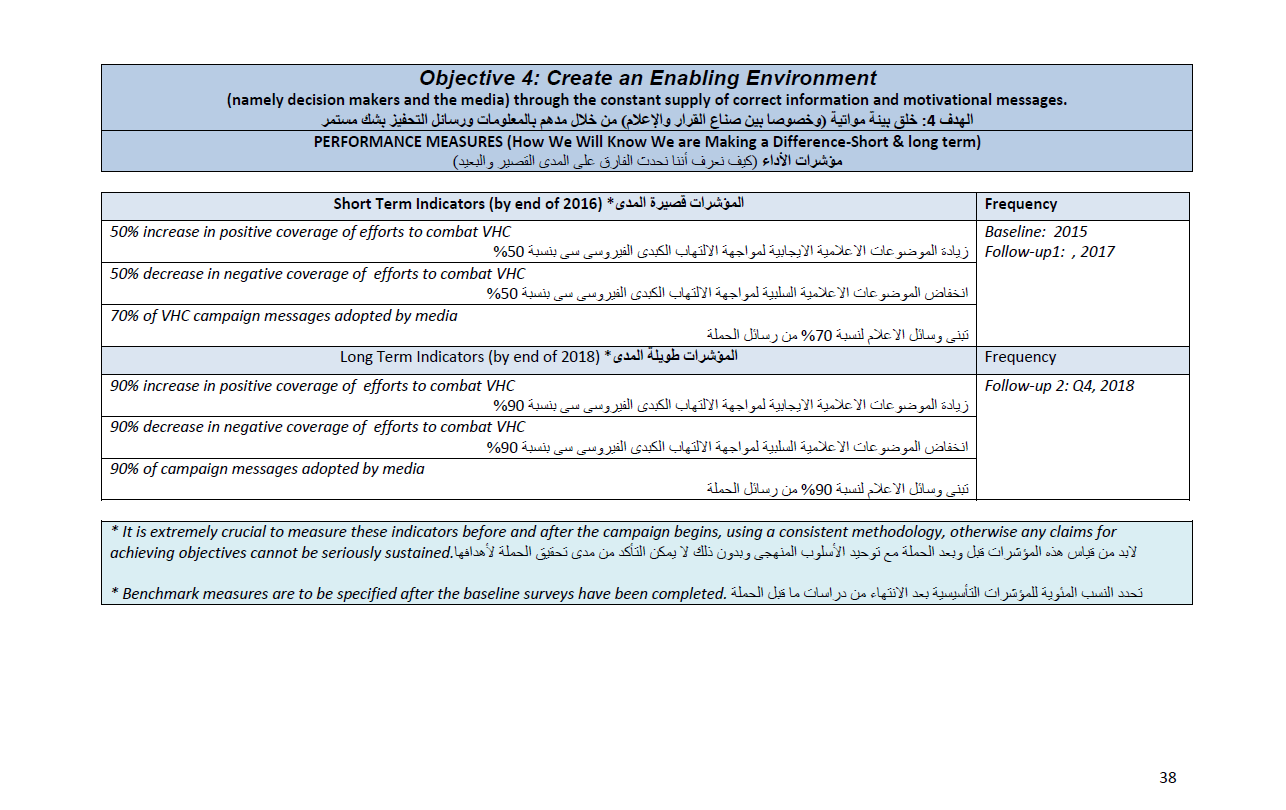

- Enhance the enabling environment (namely decision makers and the media) through the constant supply of correct information and motivational messages.

Audience segmentation

- The general public

- Individuals living with HCV and their families

- Healthcare providers

- The media, opinion leaders and decision makers

Summary of recommended key approaches for target segments:

The General Public:

- Baseline and follow-up KAP and media habits surveys as well as Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) utilized in message development and pretesting.

- TV & Radio public service announcements

- TV & Radio talk shows, popular/health/women/children’s programs

- Special events including World Hepatitis day.

- Stickers and pamphlets at P.O.S, public transportation, and workplaces.

- Community mobilization in schools, universities, mosques, churches, NGOs, clubs, and local businesses.

- Newspaper coverage of HCV news and events.

Persons with HCV:

- Baseline and follow-up KAP and media habits surveys as well as Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) utilized in message development and pretesting.

- The internet and social media (most popular Egyptian websites and social media, in addition to websites for NCCVH, the MOHP, the national program, and WHO.)

- Upgrade, publicize and utilize the HCV hotline

- SMS to mobile phones (The national control program has a database which includes more than one million mobile phone numbers for all those who applied through the NCCVH website for the new treatment.)

- TV spots featuring celebrities and champions who have had the HCV treatment

- A series of video magazines for patients in the waiting halls of liver institute and similar health providers

Healthcare Providers:

- Establish a database for healthcare providers

- Baseline and follow-up KAP and media habits surveys as well as Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) utilized in message development and pretesting.

- Leaflets for healthcare providers specially those dealing with blood and injection.

- A special mass-mailed letter with specific actionable instructions from the Minister or other senior MOHP leadership to all those involved in injection or blood.

- Support outreach and mobilization of HCP in 5270 primary healthcare units and 450 hospitals within 5 years through supporting TOT and peer education efforts conducted by the MOHP.

- Produce one educational film that clarifies the specific steps HCP should follow for infection control (IC).

- Digital mass campaigns through SMS and the internet with essential information and instructions.

Media, Decision Makers and Other Opinion Leaders:

- Content analysis of media coverage of HCV.

- Press releases, press kits, lobbying services and story pitching to the journalists and media editors.

- Special events and news conferences to keep the media and decision makers involved.

- High-level advocacy activities including meetings and a regular newsletter to decision makers, particularly the parliamentary subcommittee on health and owners of large businesses to promote corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Highlights of the Strategy & Implementation Plan

Detailed activities, timeline, budget, expected results and responsibilities:

A special template was used to detail the above mentioned aspects of the implementation plan for each of the four objectives specified in the strategy. As can be noticed from the table of contents shown above, the plan was very detailed (44 pages). A picture of the template head is featured below:

Short and long-time indicators for all objectives:

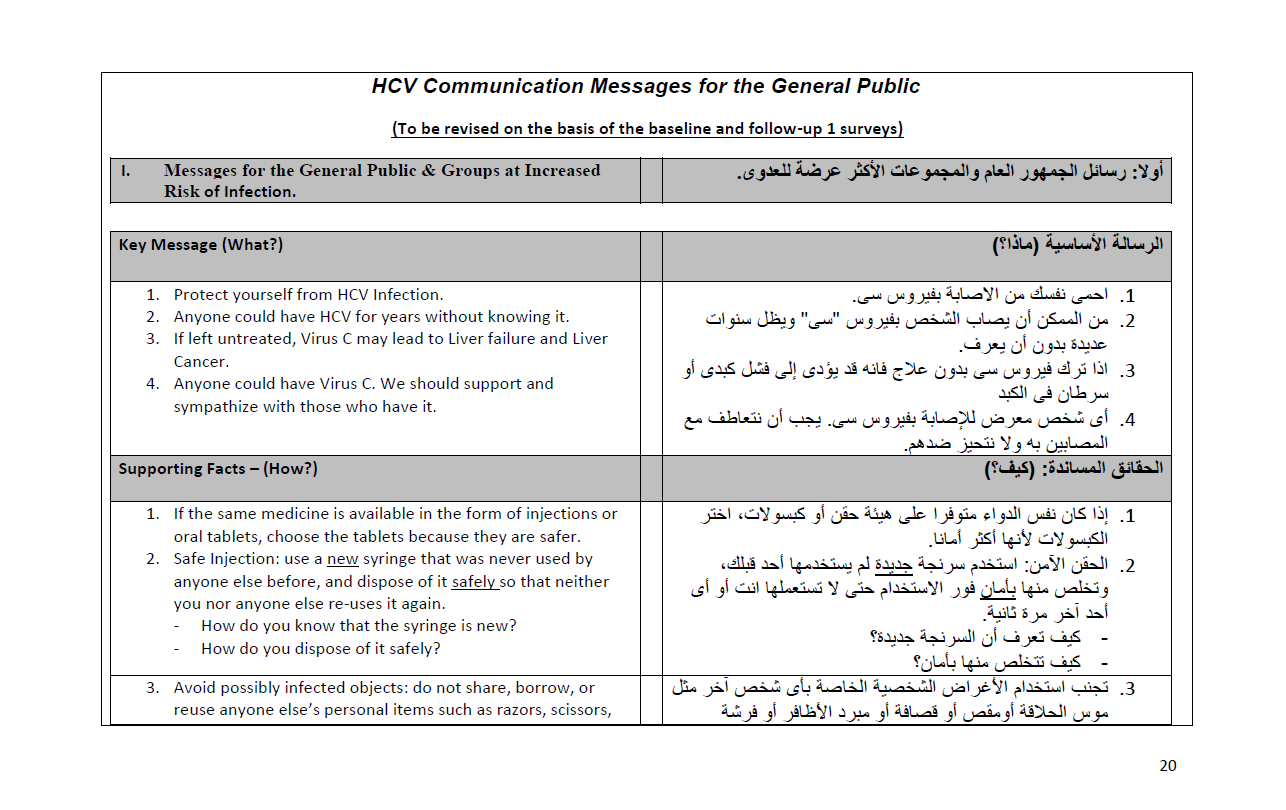

Communication Messages

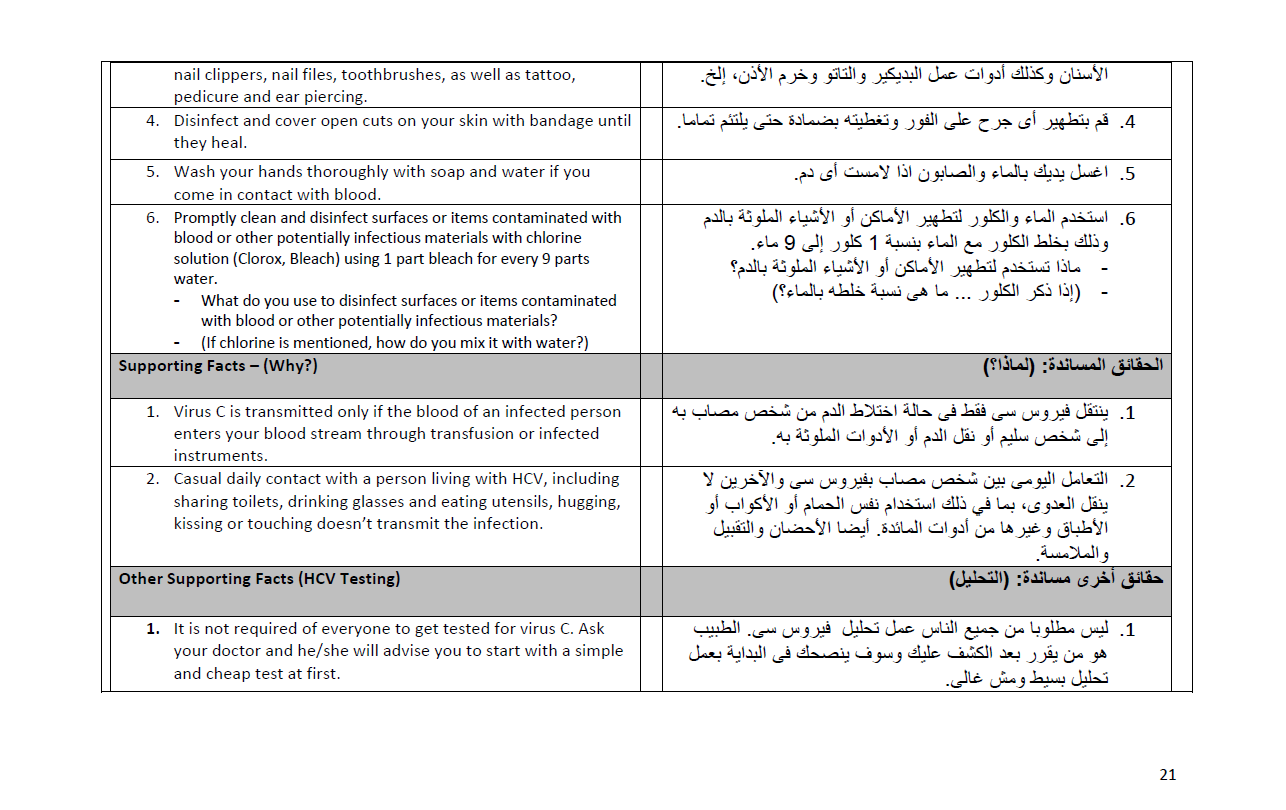

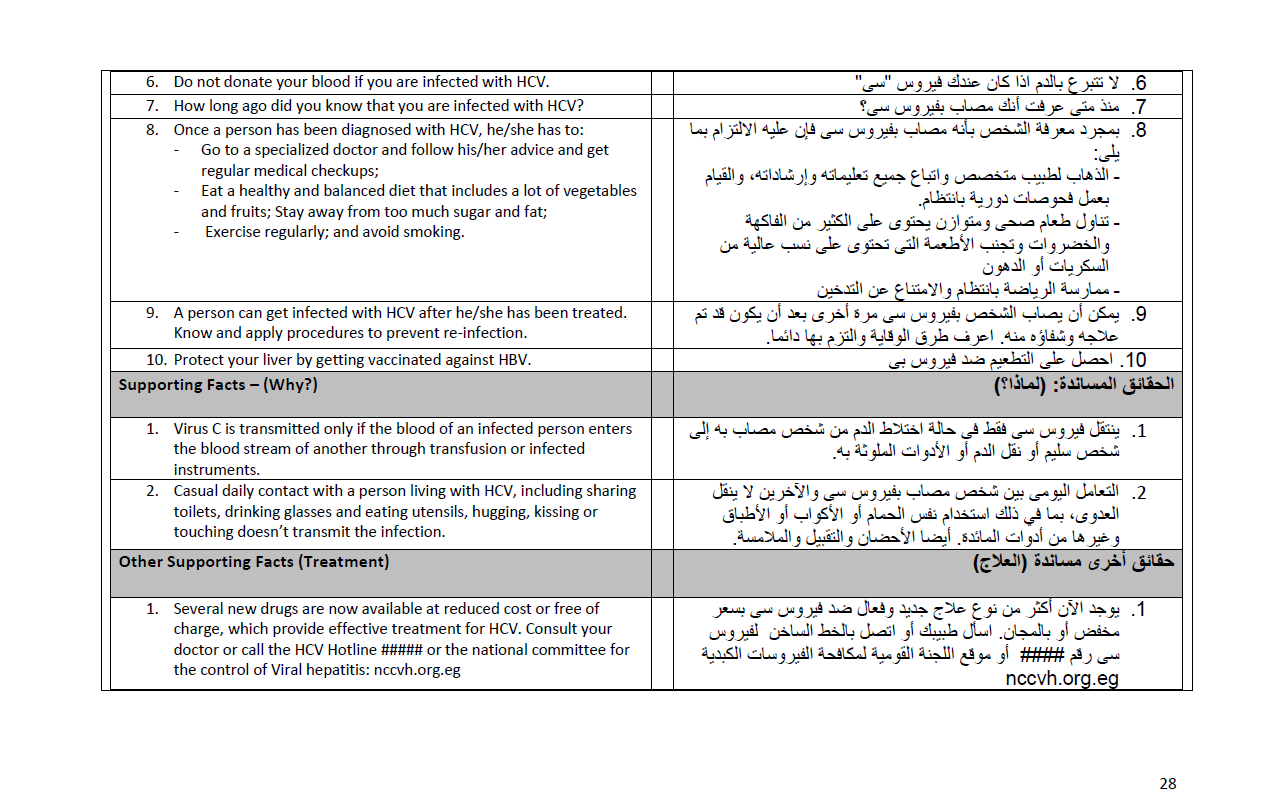

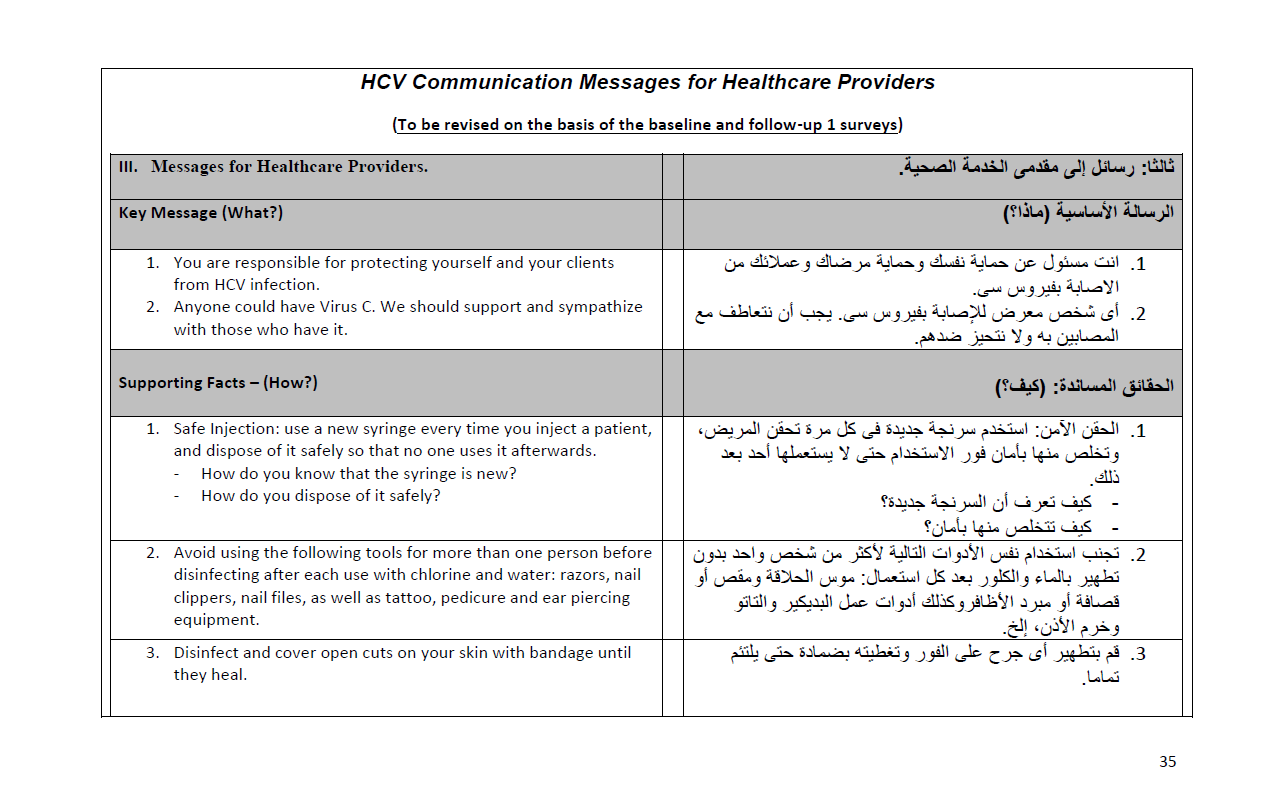

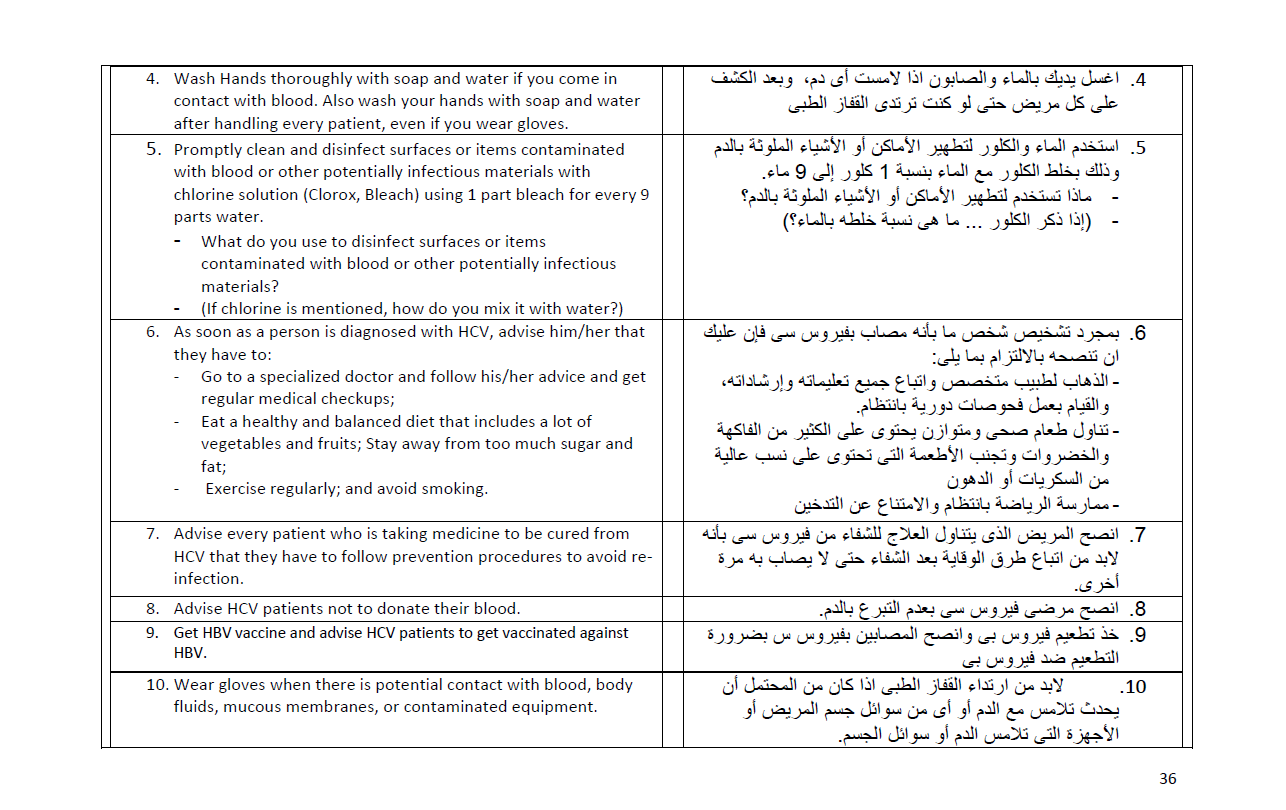

Detailed lists of messages and their supporting facts were drafted in the strategy and implementation plan. It was stressed, however that the lists were not final and that final message lists and contents are “To be revised on the basis of the baseline and follow-up 1 surveys“.

Notice that the messages are drafted in consistency with the theory and methodology outlined elsewhere in this site. For more details, please see: Theory & Methodology

A detailed feature on the baseline study and its results is here (in English): Hepatitis C Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Egypt and is here (in Arabic): Hepatitis C Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Egypt (Arabic). A description of the campaign and how it was developed on the basis of the baseline study is available here: It’s either us or virus C!