Farag Elkamel, PhD

The hieroglyph in figure (1) is of the 18th dynasty, dating between 1580-1350 B.C. It shows that polio had existed in Egypt even back then.

More recently, scientists discovered the first vaccine against polio virus in 1955. The vaccine was in the form of an injection until 1961, when an oral route of administration was discovered. In 1988, when the Global Polio Eradication Initiative began, polio paralyzed more than 1,000 children worldwide every day.

Since the polio immunization effort began in Egypt during the 1990s, the numbers of reported infections steadily decreased. Routine polio vaccination was made available at no cost from all ministry of health facilities. Regular media coverage and news reporting as well as public service announcements were intensified during periodic National Immunization Days (NIDs). Various international agencies were involved in supplying the vaccines and donating funds and technical assistance for these efforts. The number of polio cases discovered kept declining, but polio never went away from Egypt until 2005.

In fact, there was a state of alarm in 2001 that turned into panic in 2002, when the downward trend in reported polio cases was reversed, as the numbers of confirmed polio cases started to rise again. After the number of reported cases was down to 4 in 2000, an upward trend started where the number increased to 5 in 2001 and to 7 in 2002. The cases were mainly discovered in densely populated and slum areas, where it was more difficult to reach and vaccinate all children. The government’s anxiety was justified, since the World Health Organization cannot declare a country as polio free if only one case was detected. Furthermore, Egypt by then was one of only six countries in the whole world where polio was still present. What was believed to be the final inch towards polio eradication in Egypt suddenly seemed longer than a mile!

In 2002, UNICEF was called upon by the polio Technical Advisory Group, (TAG) consisting of government decision makers and international donors to support the ministry of health and population with communication aspects of the polio eradication drive. Consequently, UNICEF called upon me in 2002 to be their chief communication adviser, and gave me a free hand to review and revise the course of the campaign as I see fit.

After reviewing existing plans, I conducted a series of field visits to selected poor neighborhoods and slum areas, where some of the last cases of polio were detected, and in-depth interviews were conducted with parents and local ministry of health officials in pilot districts. In addition, we conducted a series of focus group discussions in four governorates: Cairo, Giza, Sharkia in the Delta, and Assiut in Upper Egypt. Moreover, I proposed the insertion of some key questions on polio immunization knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as questions on media habits in the assessment baseline survey which was planned to be undertaken by an independent and reputable research organization.[1]

The main issues and concerns that came out of these field visits and the survey were:

- There was too much emphasis in communication on addressing attitudes when almost all caretakers had highly positive attitudes already. Most caretakers of children who were not immunized during the last NID held positive attitudes towards immunization, yet their children weren’t immunized.

- The content of the communication campaign lacked advice to caretakers as to how to make sure that their child is not missed by the campaign. Even though the last NID was carried out door to door, some children were missed because their parents weren’t home during the visits and they didn’t designate someone else to make sure that the children would be immunized.

- Too much effort and budget were allocated to ineffective media, such as print, and too little attention was given to more effective ones, including television spots and megaphones at the community level.

- There was little use of effective community mobilization despite the low cost involved. The local health staff was lacking the necessary strategy, plan, content, and communication skills.

- Messages needed to enhance the sense of responsibility that parents should have towards their children’s health in general and immunization in particular.

- Many caretakers had other problems such as misinformation and wrong beliefs which would cause reluctance to immunize their children.

The New Strategic Directions Since 2002

While the family planning and oral rehydration cases presented earlier have achieved remarkable success with the general public using mass media campaigns with little additional help from interpersonal communication, in this instance, however, the revised communication strategy which I presented to Unicef and the Egyptian government included the following three key recommendations: (1) revise the communication strategy and media mix, (2) revise the content and message strategy and (3) use community mobilization in combination with mass media.

- Revising the communication strategy and media mix

Media habits indicators, as measured in the 2002 baseline assessment mentioned above showed that television had a much wider reach than either radio or print media. The results indicated that TV ownership had surpassed radio ownership in Egypt, contrary to what was believed by the polio program decision makers, where 93 percent of the baseline sample reported watching TV compared to 42 percent who listened to the radio. But that’s only half the story. While 68 percent watched television regularly, only 14 percent listened to the radio on a regular basis. Only 8.5 percent of the sample said that they read newspapers and magazines on a regular basis.

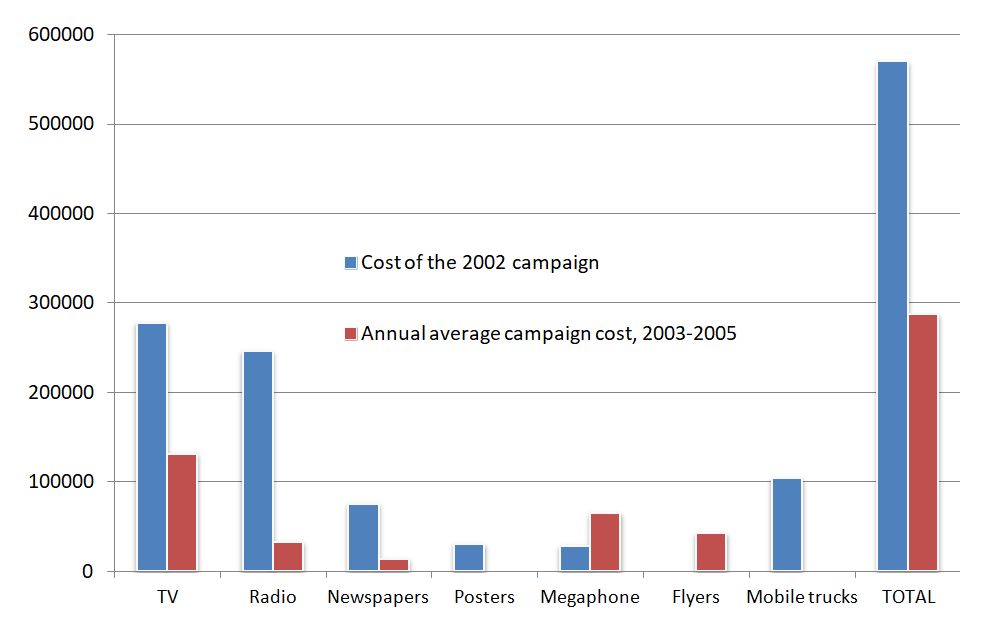

The revised communication plan changed the media mix for the campaigns from 2003 to 2005 according to the new strategy which we proposed to and was adopted by UNICEF and the ministry of health. The following comments can be made regarding the comparison between the 2002 plan and the 2003-205:

- It would have been expected that the communication budget would be increased after the catastrophic rise in the numbers of reported cases. However, the cost of the 2002 campaign was in fact higher than that in any of the following years. The average communication cost during the years 2003-2005 was 43 percent lower than that of 2002. With this relatively low cost, however major changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors were achieved, as will be discussed below.

- We revised the media mix quite significantly, where some media were dropped completely, including posters, and the uses of mobile trucks and other media were reduced such as radio and print media. Other community media were introduced for the first time, such as flyers, and the use of others such as megaphones was significantly increased.

- A strong emphasis on television continued at 40 percent of the total communication cost, but with a revised message content strategy as will be discussed later.

Table (1) Polio Communication Campaign Cost 2002-2005

| Mass/Community Media | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | Total 2003-2005 | Average 2003-2005 |

| TV | 278,321 | 80,000 | 246,500 | 70,000 | 396,500 | 132,167 |

| Radio | 51,425 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 100,000 | 33,333 |

| Newspapers & Magazines | 76,091 | 24,000 | 17,857 | 0 | 41,857 | 13,952 |

| Posters | 31,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Megaphone | 29,843 | 14,922 | 176,658 | 5.536 | 197,116 | 65,705 |

| Flyers | 0 | 125,000 | 0 | 3,460 | 128,460 | 42,820 |

| Mobile Trucks | 104,399 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TOTAL | 571,079 | 343,922 | 441,015 | 78,996 | 863,933 | 287,977 |

[i] El- Zanaty & Associates, National Immunization Day For The Eradication Of Polio In Egypt Final Assessment, Unicef, 2005

2. Revising the Message content strategy

Field reports have showed that there are some negative attitudes and behavioral shortcomings such as the public reluctance and ignorance of the importance of routine immunization, spread of some rumors and misconceptions regarding the after effects of the vaccine. Other caretakers don’t cooperate with vaccination teams particularly if they have already given their children one or two doses through the routine immunization program.

In addition to these reports, we analyzed the results of the national baseline survey which included a total of 2048 households in July 2002[3]. The situation as found in this 2002 baseline survey follows, but phrased in the “Knowledge and Social Change” theoretical framework[4] terminology and classifications as these were the basis for planning the communication campaigns 2003-2005.

“Awareness” Knowledge

- Knowledge about the polio disease: there was no issue with this facet of knowledge as 99.6 percent stated that they had heard about polio before. However, 12 percent of care takers also said that polio vaccination has harmful side effects. The high level of awareness may be therefore misleading.

“How-to” Knowledge

- Respondents remain somewhat confused about the issue of the maximum number of polio vaccine shots that a child can take. 42 percent of the 2002 respondents couldn’t agree with the statement that there was no maximum number of doses for the polio vaccine. This finding may explain the reluctance of some parents to get their children immunized in NIDs if they think that their child has already taken “enough” rounds of immunization.

- Despite the central importance of the message that children should get the polio vaccine starting from day one after they are born, 13 percent of caretakers don’t have this information. A clarification of this issue should be one of the key messages to target in future mass media and social mobilization campaigns, but more importantly television messages as this medium appears to set the agenda and give added credibility to messages communicated through various other media.

- With regards to the dangers associated with delaying one dose of the polio vaccine. 49 percent of respondents stated that nothing would happen if the child delayed taking one dose. The percentage of caretakers who said that such delay would cause the child to get polio is only 26 percent

Principles Knowledge

- It is comforting that 83 percent of the sample mentioned that extra doses of the polio vaccine will not harm the child. However, we need to worry about the remaining 17 percent.

- Regarding the possibility of child vaccination in case they have fever or diarrhea, 76 percent of the respondents mentioned that the child could be vaccinated while having fever and less than one quarter of respondents mentioned that he/she could not be vaccinated.

- Regarding the immunization of children against polio while having diarrhea, slightly less than two-thirds of respondents mentioned that the child should be re-vaccinated, while 32 percent mentioned that he/she shouldn’t.

- With regards to whether or not a child should be vaccinated even if he/she had just eaten a meal, only 73 percent answered the question positively. Once again, we should worry about the remaining 27 percent.

Message strategy and content recommendations

- Television alone accounts for 87 percent of caretakers’ knowledge of polio immunization. All other sources of information, combined, contribute 44 percent (multiple responses were permitted). While this skewed distribution reflects the nature of television itself as well as the near universal access that it enjoys, it may however indicate a need to explore ways to improve the utilization of other means as well, particularly community-level outlets.

- General awareness of polio immunization and its importance is quite high among caretakers: 99.6 percent had heard about polio before, 96 percent heard of NIDs, and 95 percent heard of the last NID. However, the level of “how-to-knowledge” among caretakers is one that needs a sharper focus in future campaigns, as 40 percent acknowledged that they didn’t know that a child should take the polio vaccine from the first day after birth, and 50 percent said that they didn’t know that a child could be immunized even if he/she had fever.

- Caretakers also have problems with some aspects of “principles-knowledge”, which can relate to their persuasion to cooperate with vaccination teams. For example, 51 percent of respondents are confused about the maximum number of polio doses a child could take. A clear message on this issue is required.

- Certain key messages still need to be stressed in order to reduce the numbers of children who are missed by the NIDs. Such messages may include ones such as:

- “Children must be immunized during the NID, even if they had received all of their regular doses before”,

- “The polio vaccine has no side effects”,

- “The polio vaccine can be taken even if the child has fever or diarrhea”.

- Also, exact dates and locations for the NID should be repeatedly promoted through all campaign channels and community outlets.

- In addition, practical advice to caretakers is needed regarding possible ways to make sure that the child is immunized during the NID’s home visits. Messages could propose for example the possibility to leave the child with a family member, a neighbor, or a friend, or to take them to a fixed post for immunization.

Attitudes

- There is a universally positive attitude towards polio immunization. However:

- More respondents were likely to believe that NIDs are not essential, and that routine doses were sufficient among those with higher socioeconomic status, as 8 percent of university graduates gave such an answer, compared with only 2 percent of those with elementary school education or less.

- Campaign messages need not dwell too much on attitude issues, but on solid and clear assurances that they need not fear repeated polio vaccinations.

Practices

- The majority of missed cases in the last NID could have been immunized, but unfortunately weren’t because of quite avoidable causes. For example, in two thirds of the cases, the cause was either that the vaccinators didn’t show up, the caretaker didn’t know that there was a door to door vaccination campaign, or that neither caretaker nor child was home during the time vaccinators came to the house.

- Communication messages should stress the importance of leaving the child at home or at a family member or close relative or a friend’s home on the designated NID. The message should ask caretakers to take the child on the same day to a fixed vaccination site if it was impossible to do the above.

3. Strengthening Community Mobilization

- Developing Planning tools for organizing community awareness campaigns

- Building MOHP capacities for planning and implementing community social mobilization activities (training, TOT, manuals)

- Institutionalizing community social mobilization within the MOHP micro planning process

Tailor-made training plans, curricula, and workshops were organized for ministry of health and volunteer staff. The objective was to empower them with communication skills to convey specific messages to local high-risk communities. Community mobilization was targeted to reaching families through local outlets, namely mosques, churches, schools, megaphones, health centers and local businesses.

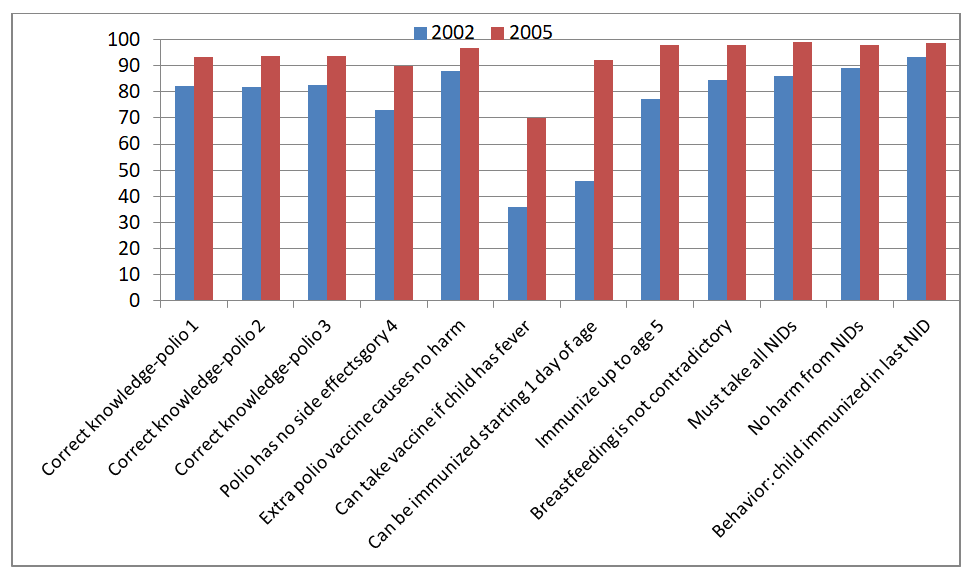

Impact on Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors

As mentioned above, our recommendation was to go past the focus on attitude change and to focus on other content that would be more conducive to causing behavioral change, since attitudes towards polio immunization were already quite positive (97.3 percent) in 2002. Despite media campaign focus on other content, attitudes remained quite positive in 2005 (99.2%). Quite significant gains however were made in other aspects of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior between 2002 and 2005, as shown below:

Table (2) Polio Immunization Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviors of Caretakers (%), Egypt 2002-2005

| Knowledge, Attitudes and Behavior Indicators | 2002 | 2005 |

| Correct knowledge-polio 1 | 82.2 | 96.3 |

| Correct knowledge-polio 2 | 82 | 93.8 |

| Correct knowledge-polio 3 | 82.6 | 93.6 |

| Polio has no side effects | 73.1 | 90 |

| Extra polio vaccine causes no harm | 88.1 | 96.6 |

| Can take vaccine if child has fever | 35.9 | 70 |

| Can be immunized starting 1 day of age | 46 | 92.1 |

| Immunize up to age 5 | 77.1 | 98 |

| Breastfeeding is not contradictory | 84.7 | 97.9 |

| Must take all NIDs | 86.2 | 99 |

| No harm from NIDs | 89.3 | 98.1 |

| Behavior: child immunized in last NID | 93.4 | 98.6 |

Impact on Polio Eradication:

Confirmed Cases of Polio started to decline in 2003 and then completely disappeared in 2005. Egypt was declared polio free by the Minister of Health and Population on August 29, 2005, and by UNICEF/WHO on February 1, 2006. It’s perhaps the first time Egypt was polio free in several thousand years!

Table (3) Annual Number of Confirmed Cases of Poliomyelitis in Egypt: 1997-2008

| Year | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

| Cases | 14 | 35 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Year | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| Cases | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Cost-effectiveness of Media Channels and Formats

Studies of cost effectiveness of communication campaigns are quite rare, since even studies of their impact are themselves not common. The evaluation of the polio campaigns, however went this extra mile, as a follow up survey was dedicated to this interesting investigation.

In the cost-effectiveness analysis, the effectiveness of the alternative media means are measured and compared through cost-effectiveness ratios. The cost-effectiveness ratio of a particular medium is calculated by dividing the cost of conducting this campaign, expressed in monetary terms, by its effectiveness, expressed in non-monetary terms. In the current investigation, this ratio can be used to estimate the cost of the media mean per “motivated” caretaker. The term motivated caretaker refers to the caretakers who are motivated by the media mean to immunize their eligible children. The medium with the smallest ratios are considered to be the most cost-effective. Thus, for the purpose of this cost-effectiveness investigation, cost will be determined for mass media and interpersonal communication. Then, the cost-effectiveness of each media campaign can be broken down by type of media used.[5]

In early October, 2005, a follow-up survey was conducted following the September,

2005’s NID. This follow-up survey was designed to maximize opportunities for meaningful comparisons among the type of polio media campaigns in terms of exposure and cost. An important improvement was made in the follow-up questionnaire by asking the surveyed caretaker to identify the key media type that motivated him/her to immunize his/her children in the September, 2005’s NID. This type of question was not included in the final assessment survey.

Table (3) shows the number of motivated caretakers to each type of media based on the results of the follow-up survey conducted after the September, 2005 polio campaign. The total number of caretakers surveyed in the follow-up survey was 1,549. According to the figures in the table, 72 percent of the caretakers in the survey who immunized their children were primarily motivated by the TV spots, 2 percent were motivated by the TV programs, 2 percent by the radio, and 7 percent by the megaphones.[6]

Table (4) Cost and Number of Motivated Caretakers (Follow-up Survey 2005)

| Media | TV Spots | Regular TV Programs | Radio | Megaphones |

| No. of Motivated Caretakers (survey) | 1,119 | 25 | 32 | 114 |

| Estimated number of motivated caretakers (population) | 6,078,519 | 135,803 | 173,827 | 619,259 |

| Average cost per 1,000 motivated caretakers in LE | 4.42 | 78.36 | 48.4 | 20.36 |

To estimate the number of caretakers in the September, 2005 polio campaign who were motivated by each type of media, the following methodology was used. The number of immunized children during the September, 2005 NID was 11 million children, while the number of children immunized in the sample surveyed in the follow-up survey was estimated to be 2,025 children and the number of caretakers in that sample was 1,549 caretakers. This information was used to obtain rough estimations of the number of caretakers who were motivated by the different media means to immunize their children. Denote C as the number of caretakers motivated by the media mean and to immunize their children in Egypt, and c is that number in the sample survey, then an estimation of C can be obtained using the following equation: C=c×11,000,000/2,025. The second row in the table presents the estimation of the number of motivated caretakers by each type of media.

To compare the effectiveness of the different types of media used, the cost-effectiveness ratio of each media mean was derived by dividing the average cost per campaign of the media used by the estimated number of motivated caretakers. The last row of the table shows the cost-effectiveness ratios per 1000 responding caretakers for each type of media.

As shown in this table, the media with the best cost-effectiveness indicator is the TV spots (LE 4.42 per 1000 motivated caretakers), followed by the megaphones (LE 20.36 per1000 motivated caretakers), radio (LE 48.4 per 1000 motivated caretakers), and finally the regular TV programs (LE 78.36 per 1000 motivated caretakers). According to these results, the TV spots are the most cost–effective medium, while regular TV programs are the worst in terms of cost ratio. It should be noted, however, that the cost of TV spots does not include the cost of air time, which was donated by the state-owned television channels.

[1] El- Zanaty & Associates, Support to National Communication Polio Plan

Baseline Survey, Unicef 2002. https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/EGY_2002_005.pdf

[2] El- Zanaty & Associates, iNational Immunization Day For The Eradication Of Polio In Egypt Final Assessment, Unicef, 2005

[3] El-Zanaty 2002

[4] Elkamel 1981

[5] Zanaty 2005, p.55

[6] Ibid., p. 60